|

| Classical Fake Book - 2nd Edition

Fake Book [Fake Book] - Facile

Hal Leonard

(Over 850 Classical Themes and Melodies in the Original Keys) For C instrument. ...(+)

(Over 850 Classical

Themes and Melodies in

the Original Keys) For C

instrument. Format:

fakebook (spiral bound).

With vocal melody

(excerpts) and chord

names. Lassical. Series:

Hal Leonard Fake Books.

646 pages. 9x12 inches.

Published by Hal Leonard.

(8)$49.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Transcriptions of Lieder

Piano seul

Carl Fischer

Chamber Music Piano SKU: CF.PL1056 Composed by Clara Wieck-Schumann, Fran...(+)

Chamber Music Piano

SKU: CF.PL1056

Composed by Clara

Wieck-Schumann, Franz

Schubert, and Robert

Schumann. Edited by

Nicholas Hopkins.

Collection. With Standard

notation. 128 pages. Carl

Fischer Music #PL1056.

Published by Carl Fischer

Music (CF.PL1056).

ISBN 9781491153390.

UPC: 680160910892.

Transcribed by Franz

Liszt. Introduction

It is true that Schubert

himself is somewhat to

blame for the very

unsatisfactory manner in

which his admirable piano

pieces are treated. He

was too immoderately

productive, wrote

incessantly, mixing

insignificant with

important things, grand

things with mediocre

work, paid no heed to

criticism, and always

soared on his wings. Like

a bird in the air, he

lived in music and sang

in angelic fashion.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Dr. S. Lebert (1868) Of

those compositions that

greatly interest me,

there are only Chopin's

and yours. --Franz Liszt,

letter to Robert Schumann

(1838) She [Clara

Schumann] was astounded

at hearing me. Her

compositions are really

very remarkable,

especially for a woman.

There is a hundred times

more creativity and real

feeling in them than in

all the past and present

fantasias by Thalberg.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Marie d'Agoult (1838)

Chretien Urhan

(1790-1845) was a

Belgian-born violinist,

organist and composer who

flourished in the musical

life of Paris in the

early nineteenth century.

According to various

accounts, he was deeply

religious, harshly

ascetic and wildly

eccentric, though revered

by many important and

influential members of

the Parisian musical

community. Regrettably,

history has forgotten

Urhan's many musical

achievements, the most

important of which was

arguably his pioneering

work in promoting the

music of Franz Schubert.

He devoted much of his

energies to championing

Schubert's music, which

at the time was unknown

outside of Vienna.

Undoubtedly, Urhan was

responsible for

stimulating this

enthusiasm in Franz

Liszt; Liszt regularly

heard Urhan's organ

playing in the

St.-Vincent-de-Paul

church in Paris, and the

two became personal

acquaintances. At

eighteen years of age,

Liszt was on the verge of

establishing himself as

the foremost pianist in

Europe, and this

awakening to Schubert's

music would prove to be a

profound experience.

Liszt's first travels

outside of his native

provincial Hungary were

to Vienna in 1821-1823,

where his father enrolled

him in studies with Carl

Czerny (piano) and

Antonio Salieri (music

theory). Both men had

important involvements

with Schubert; Czerny

(like Urhan) as performer

and advocate of

Schubert's music and

Salieri as his theory and

composition teacher from

1813-1817. Curiously,

Liszt and Schubert never

met personally, despite

their geographical

proximity in Vienna

during these years.

Inevitably, legends later

arose that the two had

been personal

acquaintances, although

Liszt would dismiss these

as fallacious: I never

knew Schubert personally,

he was once quoted as

saying. Liszt's initial

exposure to Schubert's

music was the Lieder,

what Urhan prized most of

all. He accompanied the

tenor Benedict

Randhartinger in numerous

performances of

Schubert's Lieder and

then, perhaps realizing

that he could benefit the

composer more on his own

terms, transcribed a

number of the Lieder for

piano solo. Many of these

transcriptions he would

perform himself on

concert tour during the

so-called Glanzzeit, or

time of splendor from

1839-1847. This publicity

did much to promote

reception of Schubert's

music throughout Europe.

Once Liszt retired from

the concert stage and

settled in Weimar as a

conductor in the 1840s,

he continued to perform

Schubert's orchestral

music, his Symphony No. 9

being a particular

favorite, and is credited

with giving the world

premiere performance of

Schubert's opera Alfonso

und Estrella in 1854. At

this time, he

contemplated writing a

biography of the

composer, which

regrettably remained

uncompleted. Liszt's

devotion to Schubert

would never waver.

Liszt's relationship with

Robert and Clara Schumann

was far different and far

more complicated; by

contrast, they were all

personal acquaintances.

What began as a

relationship of mutual

respect and admiration

soon deteriorated into

one of jealousy and

hostility, particularly

on the Schumann's part.

Liszt's initial contact

with Robert's music

happened long before they

had met personally, when

Liszt published an

analysis of Schumann's

piano music for the

Gazette musicale in 1837,

a gesture that earned

Robert's deep

appreciation. In the

following year Clara met

Liszt during a concert

tour in Vienna and

presented him with more

of Schumann's piano

music. Clara and her

father Friedrich Wieck,

who accompanied Clara on

her concert tours, were

quite taken by Liszt: We

have heard Liszt. He can

be compared to no other

player...he arouses

fright and astonishment.

His appearance at the

piano is indescribable.

He is an original...he is

absorbed by the piano.

Liszt, too, was impressed

with Clara--at first the

energy, intelligence and

accuracy of her piano

playing and later her

compositions--to the

extent that he dedicated

to her the 1838 version

of his Etudes d'execution

transcendante d'apres

Paganini. Liszt had a

closer personal

relationship with Clara

than with Robert until

the two men finally met

in 1840. Schumann was

astounded by Liszt's

piano playing. He wrote

to Clara that Liszt had

played like a god and had

inspired indescribable

furor of applause. His

review of Liszt even

included a heroic

personification with

Napoleon. In Leipzig,

Schumann was deeply

impressed with Liszt's

interpretations of his

Noveletten, Op. 21 and

Fantasy in C Major, Op.

17 (dedicated to Liszt),

enthusiastically

observing that, I feel as

if I had known you twenty

years. Yet a variety of

events followed that

diminished Liszt's glory

in the eyes of the

Schumanns. They became

critical of the cult-like

atmosphere that arose

around his recitals, or

Lisztomania as it came to

be called; conceivably,

this could be attributed

to professional jealousy.

Clara, in particular,

came to loathe Liszt,

noting in a letter to

Joseph Joachim, I despise

Liszt from the depths of

my soul. She recorded a

stunning diary entry a

day after Liszt's death,

in which she noted, He

was an eminent keyboard

virtuoso, but a dangerous

example for the

young...As a composer he

was terrible. By

contrast, Liszt did not

share in these negative

sentiments; no evidence

suggests that he had any

ill-regard for the

Schumanns. In Weimar, he

did much to promote

Schumann's music,

conducting performances

of his Scenes from Faust

and Manfred, during a

time in which few

orchestras expressed

interest, and premiered

his opera Genoveva. He

later arranged a benefit

concert for Clara

following Robert's death,

featuring Clara as

soloist in Robert's Piano

Concerto, an event that

must have been

exhilarating to witness.

Regardless, her opinion

of him would never

change, despite his

repeated gestures of

courtesy and respect.

Liszt's relationship with

Schubert was a spiritual

one, with music being the

one and only link between

the two men. That with

the Schumanns was

personal, with music

influenced by a hero

worship that would

aggravate the

relationship over time.

Nonetheless, Liszt would

remain devoted to and

enthusiastic for the

music and achievements of

these composers. He would

be a vital force in

disseminating their music

to a wider audience, as

he would be with many

other composers

throughout his career.

His primary means for

accomplishing this was

the piano transcription.

Liszt and the

Transcription

Transcription versus

Paraphrase Transcription

and paraphrase were

popular terms in

nineteenth-century music,

although certainly not

unique to this period.

Musicians understood that

there were clear

distinctions between

these two terms, but as

is often the case these

distinctions could be

blurred. Transcription,

literally writing over,

entails reworking or

adapting a piece of music

for a performance medium

different from that of

its original; arrangement

is a possible synonym.

Adapting is a key part of

this process, for the

success of a

transcription relies on

the transcriber's ability

to adapt the piece to the

different medium. As a

result, the pre-existing

material is generally

kept intact, recognizable

and intelligible; it is

strict, literal,

objective. Contextual

meaning is maintained in

the process, as are

elements of style and

form. Paraphrase, by

contrast, implies

restating something in a

different manner, as in a

rewording of a document

for reasons of clarity.

In nineteenth-century

music, paraphrasing

indicated elaborating a

piece for purposes of

expressive virtuosity,

often as a vehicle for

showmanship. Variation is

an important element, for

the source material may

be varied as much as the

paraphraser's imagination

will allow; its purpose

is metamorphosis.

Transcription is adapting

and arranging;

paraphrasing is

transforming and

reworking. Transcription

preserves the style of

the original; paraphrase

absorbs the original into

a different style.

Transcription highlights

the original composer;

paraphrase highlights the

paraphraser.

Approximately half of

Liszt's compositional

output falls under the

category of transcription

and paraphrase; it is

noteworthy that he never

used the term

arrangement. Much of his

early compositional

activities were

transcriptions and

paraphrases of works of

other composers, such as

the symphonies of

Beethoven and Berlioz,

vocal music by Schubert,

and operas by Donizetti

and Bellini. It is

conceivable that he

focused so intently on

work of this nature early

in his career as a means

to perfect his

compositional technique,

although transcription

and paraphrase continued

well after the technique

had been mastered; this

might explain why he

drastically revised and

rewrote many of his

original compositions

from the 1830s (such as

the Transcendental Etudes

and Paganini Etudes) in

the 1850s. Charles Rosen,

a sympathetic interpreter

of Liszt's piano works,

observes, The new

revisions of the

Transcendental Etudes are

not revisions but concert

paraphrases of the old,

and their art lies in the

technique of

transformation. The

Paganini etudes are piano

transcriptions of violin

etudes, and the

Transcendental Etudes are

piano transcriptions of

piano etudes. The

principles are the same.

He concludes by noting,

Paraphrase has shaded off

into

composition...Composition

and paraphrase were not

identical for him, but

they were so closely

interwoven that

separation is impossible.

The significance of

transcription and

paraphrase for Liszt the

composer cannot be

overstated, and the

mutual influence of each

needs to be better

understood. Undoubtedly,

Liszt the composer as we

know him today would be

far different had he not

devoted so much of his

career to transcribing

and paraphrasing the

music of others. He was

perhaps one of the first

composers to contend that

transcription and

paraphrase could be

genuine art forms on

equal par with original

pieces; he even claimed

to be the first to use

these two terms to

describe these classes of

arrangements. Despite the

success that Liszt

achieved with this type

of work, others viewed it

with circumspection and

criticism. Robert

Schumann, although deeply

impressed with Liszt's

keyboard virtuosity, was

harsh in his criticisms

of the transcriptions.

Schumann interpreted them

as indicators that

Liszt's virtuosity had

hindered his

compositional development

and suggested that Liszt

transcribed the music of

others to compensate for

his own compositional

deficiencies.

Nonetheless, Liszt's

piano transcriptions,

what he sometimes called

partitions de piano (or

piano scores), were

instrumental in promoting

composers whose music was

unknown at the time or

inaccessible in areas

outside of major European

capitals, areas that

Liszt willingly toured

during his Glanzzeit. To

this end, the

transcriptions had to be

literal arrangements for

the piano; a Beethoven

symphony could not be

introduced to an

unknowing audience if its

music had been subjected

to imaginative

elaborations and

variations. The same

would be true of the 1833

transcription of

Berlioz's Symphonie

fantastique (composed

only three years

earlier), the

astonishingly novel

content of which would

necessitate a literal and

intelligible rendering.

Opera, usually more

popular and accessible

for the general public,

was a different matter,

and in this realm Liszt

could paraphrase the

original and manipulate

it as his imagination

would allow without

jeopardizing its

reception; hence, the

paraphrases on the operas

of Bellini, Donizetti,

Mozart, Meyerbeer and

Verdi. Reminiscence was

another term coined by

Liszt for the opera

paraphrases, as if the

composer were reminiscing

at the keyboard following

a memorable evening at

the opera. Illustration

(reserved on two

occasions for Meyerbeer)

and fantasy were

additional terms. The

operas of Wagner were

exceptions. His music was

less suited to paraphrase

due to its general lack

of familiarity at the

time. Transcription of

Wagner's music was thus

obligatory, as it was of

Beethoven's and Berlioz's

music; perhaps the

composer himself insisted

on this approach. Liszt's

Lieder Transcriptions

Liszt's initial

encounters with

Schubert's music, as

mentioned previously,

were with the Lieder. His

first transcription of a

Schubert Lied was Die

Rose in 1833, followed by

Lob der Tranen in 1837.

Thirty-nine additional

transcriptions appeared

at a rapid pace over the

following three years,

and in 1846, the Schubert

Lieder transcriptions

would conclude, by which

point he had completed

fifty-eight, the most of

any composer. Critical

response to these

transcriptions was highly

favorable--aside from the

view held by

Schumann--particularly

when Liszt himself played

these pieces in concert.

Some were published

immediately by Anton

Diabelli, famous for the

theme that inspired

Beethoven's variations.

Others were published by

the Viennese publisher

Tobias Haslinger (one of

Beethoven's and

Schubert's publishers in

the 1820s), who sold his

reserves so quickly that

he would repeatedly plead

for more. However,

Liszt's enthusiasm for

work of this nature soon

became exhausted, as he

noted in a letter of 1839

to the publisher

Breitkopf und Hartel:

That good Haslinger

overwhelms me with

Schubert. I have just

sent him twenty-four new

songs (Schwanengesang and

Winterreise), and for the

moment I am rather tired

of this work. Haslinger

was justified in his

demands, for the Schubert

transcriptions were

received with great

enthusiasm. One Gottfried

Wilhelm Fink, then editor

of the Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung,

observed of these

transcriptions: Nothing

in recent memory has

caused such sensation and

enjoyment in both

pianists and audiences as

these arrangements...The

demand for them has in no

way been satisfied; and

it will not be until

these arrangements are

seen on pianos

everywhere. They have

indeed made quite a

splash. Eduard Hanslick,

never a sympathetic

critic of Liszt's music,

acknowledged thirty years

after the fact that,

Liszt's transcriptions of

Schubert Lieder were

epoch-making. There was

hardly a concert in which

Liszt did not have to

play one or two of

them--even when they were

not listed on the

program. These

transcriptions quickly

became some of his most

sough-after pieces,

despite their extreme

technical demands.

Leading pianists of the

day, such as Clara Wieck

and Sigismond Thalberg,

incorporated them into

their concert programs

immediately upon

publication. Moreover,

the transcriptions would

serve as inspirations for

other composers, such as

Stephen Heller, Cesar

Franck and later Leopold

Godowsky, all of whom

produced their own

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder. Liszt

would transcribe the

Lieder of other composers

as well, including those

by Mendelssohn, Chopin,

Anton Rubinstein and even

himself. Robert Schumann,

of course, would not be

ignored. The first

transcription of a

Schumann Lied was the

celebrated Widmung from

Myrten in 1848, the only

Schumann transcription

that Liszt completed

during the composer's

lifetime. (Regrettably,

there is no evidence of

Schumann's regard of this

transcription, or even if

he was aware of it.) From

the years 1848-1881,

Liszt transcribed twelve

of Robert Schumann's

Lieder (including one

orchestral Lied) and

three of Clara (one from

each of her three

published Lieder cycles);

he would transcribe no

other works of these two

composers. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions,

contrary to those of

Schubert, are literal

arrangements, posing, in

general, far fewer

demands on the pianist's

technique. They are

comparatively less

imaginative in their

treatment of the original

material. Additionally,

they seem to have been

less valued in their day

than the Schubert

transcriptions, and it is

noteworthy that none of

the Schumann

transcriptions bear

dedications, as most of

the Schubert

transcriptions do. The

greatest challenge posed

by Lieder transcriptions,

regardless of the

composer or the nature of

the transcription, was to

combine the vocal and

piano parts of the

original such that the

character of each would

be preserved, a challenge

unique to this form of

transcription. Each part

had to be intact and

aurally recognizable, the

vocal line in particular.

Complications could be

manifold in a Lied that

featured dissimilar

parts, such as Schubert's

Auf dem Wasser zu singen,

whose piano accompaniment

depicts the rocking of

the boat on the

shimmering waves while

the vocal line reflects

on the passing of time.

Similar complications

would be encountered in

Gretchen am Spinnrade, in

which the ubiquitous

sixteenth-note pattern in

the piano's right hand

epitomizes the

ever-turning spinning

wheel over which the

soprano voice expresses

feelings of longing and

heartache. The resulting

transcriptions for solo

piano would place

exceptional demands on

the pianist. The

complications would be

far less imposing in

instances in which voice

and piano were less

differentiated, as in

many of Schumann's Lieder

that Liszt transcribed.

The piano parts in these

Lieder are true

accompaniments for the

voice, providing harmonic

foundation and rhythmic

support by doubling the

vocal line throughout.

The transcriptions, thus,

are strict and literal,

with far fewer demands on

both pianist and

transcriber. In all of

Liszt's Lieder

transcriptions,

regardless of the way in

which the two parts are

combined, the melody

(i.e. the vocal line) is

invariably the focal

point; the melody should

sing on the piano, as if

it were the voice. The

piano part, although

integral to contributing

to the character of the

music, is designed to

function as

accompaniment. A singing

melody was a crucial

objective in

nineteenth-century piano

performance, which in

part might explain the

zeal in transcribing and

paraphrasing vocal music

for the piano. Friedrich

Wieck, father and teacher

of Clara Schumann,

stressed this point

repeatedly in his 1853

treatise Clavier und

Gesang (Piano and Song):

When I speak in general

of singing, I refer to

that species of singing

which is a form of

beauty, and which is a

foundation for the most

refined and most perfect

interpretation of music;

and, above all things, I

consider the culture of

beautiful tones the basis

for the finest possible

touch on the piano. In

many respects, the piano

and singing should

explain and supplement

each other. They should

mutually assist in

expressing the sublime

and the noble, in forms

of unclouded beauty. Much

of Liszt's piano music

should be interpreted

with this concept in

mind, the Lieder

transcriptions and opera

paraphrases, in

particular. To this end,

Liszt provided numerous

written instructions to

the performer to

emphasize the vocal line

in performance, with

Italian directives such

as un poco marcato il

canto, accentuato assai

il canto and ben

pronunziato il canto.

Repeated indications of

cantando,singend and

espressivo il canto

stress the significance

of the singing tone. As

an additional means of

achieving this and

providing the performer

with access to the

poetry, Liszt insisted,

at what must have been a

publishing novelty at the

time, on printing the

words of the Lied in the

music itself. Haslinger,

seemingly oblivious to

Liszt's intent, initially

printed the poems of the

early Schubert

transcriptions separately

inside the front covers.

Liszt argued that the

transcriptions must be

reprinted with the words

underlying the notes,

exactly as Schubert had

done, a request that was

honored by printing the

words above the

right-hand staff. Liszt

also incorporated a

visual scheme for

distinguishing voice and

accompaniment, influenced

perhaps by Chopin, by

notating the

accompaniment in cue

size. His transcription

of Robert Schumann's

Fruhlings Ankunft

features the vocal line

in normal size, the piano

accompaniment in reduced

size, an unmistakable

guide in a busy texture

as to which part should

be emphasized: Example 1.

Schumann-Liszt Fruhlings

Ankunft, mm. 1-2. The

same practice may be

found in the

transcription of

Schumann's An die Turen

will ich schleichen. In

this piece, the performer

must read three staves,

in which the baritone

line in the central staff

is to be shared between

the two hands based on

the stem direction of the

notes: Example 2.

Schumann-Liszt An die

Turen will ich

schleichen, mm. 1-5. This

notational practice is

extremely beneficial in

this instance, given the

challenge of reading

three staves and the

manner in which the vocal

line is performed by the

two hands. Curiously,

Liszt did not use this

practice in other

transcriptions.

Approaches in Lieder

Transcription Liszt

adopted a variety of

approaches in his Lieder

transcriptions, based on

the nature of the source

material, the ways in

which the vocal and piano

parts could be combined

and the ways in which the

vocal part could sing.

One approach, common with

strophic Lieder, in which

the vocal line would be

identical in each verse,

was to vary the register

of the vocal part. The

transcription of Lob der

Tranen, for example,

incorporates three of the

four verses of the

original Lied, with the

register of the vocal

line ascending one octave

with each verse (from low

to high), as if three

different voices were

participating. By the

conclusion, the music

encompasses the entire

range of Liszt's keyboard

to produce a stunning

climactic effect, and the

variety of register of

the vocal line provides a

welcome textural variety

in the absence of the

words. The three verses

of the transcription of

Auf dem Wasser zu singen

follow the same approach,

in which the vocal line

ascends from the tenor,

to the alto and to the

soprano registers with

each verse.

Fruhlingsglaube adopts

the opposite approach, in

which the vocal line

descends from soprano in

verse 1 to tenor in verse

2, with the second part

of verse 2 again resuming

the soprano register;

this is also the case in

Das Wandern from

Mullerlieder. Gretchen am

Spinnrade posed a unique

problem. Since the poem's

narrator is female, and

the poem represents an

expression of her longing

for her lover Faust,

variation of the vocal

line's register, strictly

speaking, would have been

impractical. For this

reason, the vocal line

remains in its original

register throughout,

relentlessly colliding

with the sixteenth-note

pattern of the

accompaniment. One

exception may be found in

the fifth and final verse

in mm. 93-112, at which

point the vocal line is

notated in a higher

register and doubled in

octaves. This sudden

textural change, one that

is readily audible, was a

strategic means to

underscore Gretchen's

mounting anxiety (My

bosom urges itself toward

him. Ah, might I grasp

and hold him! And kiss

him as I would wish, at

his kisses I should

die!). The transcription,

thus, becomes a vehicle

for maximizing the

emotional content of the

poem, an exceptional

undertaking with the

general intent of a

transcription. Registral

variation of the vocal

part also plays a crucial

role in the transcription

of Erlkonig. Goethe's

poem depicts the death of

a child who is

apprehended by a

supernatural Erlking, and

Schubert, recognizing the

dramatic nature of the

poem, carefully depicted

the characters (father,

son and Erlking) through

unique vocal writing and

accompaniment patterns:

the Lied is a dramatic

entity. Liszt, in turn,

followed Schubert's

characterization in this

literal transcription,

yet took it an additional

step by placing the

register of the father's

vocal line in the

baritone range, that of

the son in the soprano

range and that of the

Erlking in the highest

register, options that

would not have been

available in the version

for voice and piano.

Additionally, Liszt

labeled each appearance

of each character in the

score, a means for

guiding the performer in

interpreting the dramatic

qualities of the Lied. As

a result, the drama and

energy of the poem are

enhanced in this

transcription; as with

Gretchen am Spinnrade,

the transcriber has

maximized the content of

the original. Elaboration

may be found in certain

Lieder transcriptions

that expand the

performance to a level of

virtuosity not found in

the original; in such

cases, the transcription

approximates the

paraphrase. Schubert's Du

bist die Ruh, a paradigm

of musical simplicity,

features an uncomplicated

piano accompaniment that

is virtually identical in

each verse. In Liszt's

transcription, the

material is subjected to

a highly virtuosic

treatment that far

exceeds the original,

including a demanding

passage for the left hand

alone in the opening

measures and unique

textural writing in each

verse. The piece is a

transcription in

virtuosity; its art, as

Rosen noted, lies in the

technique of

transformation.

Elaboration may entail an

expansion of the musical

form, as in the extensive

introduction to Die

Forelle and a virtuosic

middle section (mm.

63-85), both of which are

not in the original. Also

unique to this

transcription are two

cadenzas that Liszt

composed in response to

the poetic content. The

first, in m. 93 on the

words und eh ich es

gedacht (and before I

could guess it), features

a twisted chromatic

passage that prolongs and

thereby heightens the

listener's suspense as to

the fate of the trout

(which is ultimately

caught). The second, in

m. 108 on the words

Betrogne an (and my blood

boiled as I saw the

betrayed one), features a

rush of

diminished-seventh

arpeggios in both hands,

epitomizing the poet's

rage at the fisherman for

catching the trout. Less

frequent are instances in

which the length of the

original Lied was

shortened in the

transcription, a tendency

that may be found with

certain strophic Lieder

(e.g., Der Leiermann,

Wasserflut and Das

Wandern). Another

transcription that

demonstrates Liszt's

readiness to modify the

original in the interests

of the poetic content is

Standchen, the seventh

transcription from

Schubert's

Schwanengesang. Adapted

from Act II of

Shakespeare's Cymbeline,

the poem represents the

repeated beckoning of a

man to his lover. Liszt

transformed the Lied into

a miniature drama by

transcribing the vocal

line of the first verse

in the soprano register,

that of the second verse

in the baritone register,

in effect, creating a

dialogue between the two

lovers. In mm. 71-102,

the dialogue becomes a

canon, with one voice

trailing the other like

an echo (as labeled in

the score) at the

distance of a beat. As in

other instances, the

transcription resembles

the paraphrase, and it is

perhaps for this reason

that Liszt provided an

ossia version that is

more in the nature of a

literal transcription.

The ossia version, six

measures shorter than

Schubert's original, is

less demanding

technically than the

original transcription,

thus representing an

ossia of transcription

and an ossia of piano

technique. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions, in

general, display a less

imaginative treatment of

the source material.

Elaborations are less

frequently encountered,

and virtuosity is more

restricted, as if the

passage of time had

somewhat tamed the

composer's approach to

transcriptions;

alternatively, Liszt was

eager to distance himself

from the fierce

virtuosity of his early

years. In most instances,

these transcriptions are

literal arrangements of

the source material, with

the vocal line in its

original form combined

with the accompaniment,

which often doubles the

vocal line in the

original Lied. Widmung,

the first of the Schumann

transcriptions, is one

exception in the way it

recalls the virtuosity of

the Schubert

transcriptions of the

1830s. Particularly

striking is the closing

section (mm. 58-73), in

which material of the

opening verse (right

hand) is combined with

the triplet quarter notes

(left hand) from the

second section of the

Lied (mm. 32-43), as if

the transcriber were

attempting to reconcile

the different material of

these two sections.

Fruhlingsnacht resembles

a paraphrase by

presenting each of the

two verses in differing

registers (alto for verse

1, mm. 3-19, and soprano

for verse 2, mm. 20-31)

and by concluding with a

virtuosic section that

considerably extends the

length of the original

Lied. The original

tonalities of the Lieder

were generally retained

in the transcriptions,

showing that the tonality

was an important part of

the transcription

process. The infrequent

instances of

transposition were done

for specific reasons. In

1861, Liszt transcribed

two of Schumann's Lieder,

one from Op. 36 (An den

Sonnenschein), another

from Op. 27 (Dem roten

Roslein), and merged

these two pieces in the

collection 2 Lieder; they

share only the common

tonality of A major. His

choice for combining

these two Lieder remains

unknown, but he clearly

recognized that some

tonal variety would be

needed, for which reason

Dem roten Roslein was

transposed to C>= major.

The collection features

An den Sonnenschein in A

major (with a transition

to the new tonality),

followed by Dem roten

Roslein in C>= major

(without a change of key

signature), and

concluding with a reprise

of An den Sonnenschein in

A major. A three-part

form was thus established

with tonal variety

provided by keys in third

relations (A-C>=-A); in

effect, two of Schumann's

Lieder were transcribed

into an archetypal song

without words. In other

instances, Liszt treated

tonality and tonal

organization as important

structural ingredients,

particularly in the

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder cycles,

i.e. Schwanengesang,

Winterreise a... $32.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| The Real Little Classical Fake Book - 2nd Edition

Piano seul - Intermédiaire

Hal Leonard

Composed by Various. For Piano/Keyboard. Hal Leonard Fake Books. Classical. Diff...(+)

Composed by Various. For

Piano/Keyboard. Hal

Leonard Fake Books.

Classical. Difficulty:

medium to

medium-difficult.

Fakebook. Melody line,

chord names and lyrics

(on some songs). 413

pages. Published by Hal

Leonard

$27.50 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| 3e Symphonie en ut mineur, op. 78 - Avancé

Barenreiter

Orchestra, Organ (Fl1, Fl2 , Fl3(Fl-picc), 2 Ob, EnglHn, 2 clarinet, clarinet-B,...(+)

Orchestra, Organ (Fl1,

Fl2 , Fl3(Fl-picc), 2 Ob,

EnglHn, 2 clarinet,

clarinet-B, 2 bassoon,

bassoon-Co, Hn1, Hn2 ,

Hn3(chrom.), Hn4(chrom.),

3Trp, 3trombone, timpani,

Tr-Gr, Tri, Be, Org,

piano-4ms, 2 Violin,

Viola, Cello, Double

Bass) - Level 5 SKU:

BA.BA10303-01

Composed by Camille

Saint-Saens. Edited by

Michael Stegemann. This

edition: Edition of

selected works, Urtext

edition. Linen.

Saint-Saens, Camille.

Oevres instrumentales

completes I/3. Edition of

selected works, Score.

Opus 78. Duration 39

minutes. Baerenreiter

Verlag #BA10303_01.

Published by Baerenreiter

Verlag (BA.BA10303-01).

ISBN 9790006559503. 33

x 26 cm inches. Key: C

minor. Preface: Michael

Stegemann. The

third symphony by Camille

Saint-Saens, known as the

Organ Symphony, is the

first publication in a

complete

historical-critical

edition of the French

composer's instrumental

works.

I gave

everything I was able to

give in this work. [...]

What I have done here I

will never be able to do

again.Camille Saint-Saens

was rightly proud of his

third Symphony in C minor

Op.78, dedicated to the

memory of Franz Liszt.

Called theOrgan

Symphonybecause of its

novel scoring, the work

was a commission from the

Philharmonic Society in

London, as was

Beethoven's Ninth, and

was premiered there on 19

May 1886. The first

performance in Paris

followed on 9 January

1887 and confirmed the

composer's reputation

asprobably the most

significant, and

certainly the most

independent French

symphonistof his time, as

Ludwig Finscher wrote in

MGG. In fact the work

remains the only one in

the history of that genre

in France to the present

day, composed a good half

century after the

Symphonie fantastique by

Hector Berlioz and a good

half century before

Olivier Messiaen's

Turangalila

Symphonie.

You

would think that such a

famous, much-performed

and much recorded opus

could not hold any more

secrets, but far from it:

in the first

historical-critical

edition of the Symphony,

numerous inconsistencies

and mistakes in the

Durand edition in general

use until now, have been

uncovered and corrected.

An examination and

evaluation of the sources

ranged from two early

sketches, now preserved

in Paris and Washington

(in which the Symphony

was still in B minor!)

via the autograph

manuscript and a set of

proofs corrected by

Saint-Saens himself, to

the first and subsequent

editions of the full

score and parts. The

versions for piano duet

(by Leon Roques) and for

two pianos (by the

composer himself) were

also consulted. Further

crucial information was

finally found in his

extensive correspondence,

encompassing thousands of

previously unpublished

letters. The discoveries

made in producing this

edition include the fact

that at its London

premiere, the Symphony

probably looked quite

different from its

present appearance

...

No less

exciting than the work

itself is the history of

its composition and

reception, which are

described in an extensive

foreword. With his

Symphony, Saint-Saens

entered right into the

dispute which divided

French musical life into

pro and contra Wagner in

the 1880s and 1890s. At

the same time, the work

succeeded in preserving

the balance between

tradition and modernism

in masterly fashion, as a

contemporary critic

stated:The C minor

Symphony by Saint-Saens

creates a bridge from the

past into the future,

from immortal richness to

progress, from ideas to

their

implementation.

On

19 March 1886 Saint-Saens

wrote to the London

Philharmonic Society,

which commissioned the

work:

Work on the

symphony is in full

swing. But I warn you, it

will be terrible. Here is

the precise

instrumentation: 3 flutes

/ 2 oboes / 1 cor anglais

/ 2 clarinets / 1 bass

clarinet / 2 bassoons / 1

contrabassoon / 2 natural

horns / [3 trumpets /

Saint-Saens had forgotten

these in his listing.] 2

chromatic horns / 3

trombones / 1 tuba / 3

timpani / organ / 1 piano

duet and the strings, of

course. Fortunately,

there are no harps.

Unfortunately it will be

difficult. I am doing

what I can to mitigate

the

difficulties.

As

in my 4th Concerto [for

piano] and my [1st]

Violin Sonata [in D minor

Op.75] at first glance

there appear to be just

two parts: the first

Allegro and the Adagio,

the Scherzo and the

Finale, each attacca.

This fiendish symphony

has crept up by a

semitone; it did not want

to stay in B minor, and

is now in C

minor.

It would be

a pleasure for me to

conduct this symphony.

Whether it would be a

pleasure for others to

hear it? That is the

question. It is you who

wanted it, I wash my

hands of it. I will bring

the orchestral parts

carefully corrected with

me, and if anyone wants

to give me a nice

rehearsal for the

symphony after the full

rehearsal, everything

will be fine.

When

Saint-Saens hit upon the

idea of adding an organ

and a piano to the usual

orchestral scoring is not

known. The idea of adding

an organ part to a

secular orchestral work

intended for the concert

hall was thoroughly novel

- and not without

controversy. On the other

hand, Franz Liszt, whose

music Saint-Saens'

Symphony is so close to,

had already demonstrated

that the organ could

easily be an orchestral

instrument in his

symphonic poem

Hunnenschlacht (1856/57).

There was also a model

for the piano duet part

which Saint-Saens knew

and may possibly have

used quite consciously as

an exemplar: theFantaisie

sur la Tempetefrom the

lyrical monodrama Lelio,

ou le retour a la Vie op.

14bis (1831) by Berlioz.

The name of the organist

at the premiere ist

unknown, as,

incidentally, was also

the case with many of the

later performances; the

organ part is indeed not

soloistic, but should be

understood as part of the

orchestral

texture.

In fact

the subsequent success of

the symphony seems to

have represented a kind

of breakthrough for the

composer, who was then

over 50 years of age.My

dear composer of a famous

symphony, wrote

Saint-Saens' friend and

pupil Gabriel Faure:You

will never be able to

imagine what a pleasure I

had last Sunday [at the

second performance on 16

January 1887]! And I had

the score and did not

miss a single note of

this Symphony, which will

endure much longer than

we two, even if we were

to join together our two

lifespans!

About

Barenreiter

Urtext

What can I

expect from a Barenreiter

Urtext

edition?<

/p> MUSICOLOGICA

LLY SOUND

- A

reliable musical text

based on all available

sources

- A

description of the

sources

-

Information on the

genesis and history of

the work

- Valuable

notes on performance

practice

- Includes

an introduction with

critical commentary

explaining source

discrepancies and

editorial decisions

... AND

PRACTICAL

-

Page-turns, fold-out

pages, and cues where you

need them

- A

well-presented layout and

a user-friendly

format

- Excellent

print quality

-

Superior paper and

binding

$566.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Choral Fantasia in C minor Op. 80

Breitkopf & Härtel

Woodwinds (solo: pno - choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. - 2.2.0.0. - timp - str) SKU: B...(+)

Woodwinds (solo: pno -

choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. -

2.2.0.0. - timp - str)

SKU:

BR.OB-14660-30

Urtext based on the

new Complete Edition (G.

Henle Verlag).

Composed by Ludwig van

Beethoven. Edited by

Armin Raab. Choir;

Folder.

Orchester-Bibliothek

(Orchestral Library). The

study score

(,,Studien-Edition) is

available at G. Henle

Verlag. Have a look into

EB 10546 and CHB 14660.

Solo concerto; Classical.

Set of parts. 46 pages.

Duration 16'. Breitkopf

and Haertel #OB 14660-30.

Published by Breitkopf

and Haertel

(BR.OB-14660-30). ISBN

9790004335659. 10 x 12.5

inches. All

conducting scores and

orchestral parts as well

as piano-vocal scores and

choral parts are thus

obtainable exclusively

from Breitkopf &

Hartel. The piano

reductions of Beethoven's

solo concertos and the

study scores

(,,Studien-Editionen)

remain within the

G. Henle Verlag and

can be ordered there.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Ludwig van

Beethoven komponierte

seine Missa solemnis

zwischen 1819 und 1822.

Die vorliegende

Ausgabe legt als

Hauptquelle die

Arbeitskopie der Partitur

zugrunde die Beethoven

wohl unmittelbar nach

Fertigstellung der

Komposition in Auftrag

gab. Sie ist die alteste

Abschrift des Werks und

die einzige Kopie die das

heute unvollstandige

Autograph zur Vorlage

hatte. Da die

Arbeitskopie im Zuge des

weiteren Kopierens immer

wieder selbst revidiert

und korrigiert wurde

kommt sie heute einer

Fassung letzter Hand am

nachsten. Alle

Dirigierpartituren und

Orchesterstimmen sind

exklusiv uber Breitkopf

& Hartel erhaltlich.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Beethov

ens komplexe

Veroffentlichungsstrategi

e einer gleichzeitigen

Herausgabe in England

Frankreich und

Deutschland bei der er

nach der grosstmoglichen

Verbreitung seiner Werke

trachtete wirft die

schwierige Frage nach der

richtigen Datierung der

Originalausgabe auf.

So konnte

Hans-Werner Kuthen bei

seiner Urtextausgabe der

Ouverture zu Coriolan

nachweisen dass es sich

bei der ursprunglich als

authentisch bewerteten

Quelle vom 1. September

1807 doch um einen

Nachdruck Simrocks

handelt den Beethoven in

einem Brief vom 16. Juni

1807 offensichtlich als

ein toleriertes Relikt

erwahnt. Verbindlich fur

die Neuausgabe ist allein

der Wiener Originaldruck

des Industriekontors der

vor der Simrock-Ausgabe

entstanden sein muss. Die

Neubewertung der Quellen

brachte schliesslich auch

Anderungen in der

Artikulation mit sich.

$65.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| Choral Fantasia in C minor Op. 80

Breitkopf & Härtel

Violin 2 (solo: pno - choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. - 2.2.0.0. - timp - str) SKU: BR...(+)

Violin 2 (solo: pno -

choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. -

2.2.0.0. - timp - str)

SKU:

BR.OB-14660-16

Urtext based on the

new Complete Edition (G.

Henle Verlag).

Composed by Ludwig van

Beethoven. Edited by

Armin Raab. Choir;

stapled.

Orchester-Bibliothek

(Orchestral Library). The

study score

(,,Studien-Edition) is

available at G. Henle

Verlag. Have a look into

EB 10546 and CHB 14660.

Solo concerto; Classical.

Part. 8 pages. Duration

16'. Breitkopf and

Haertel #OB 14660-16.

Published by Breitkopf

and Haertel

(BR.OB-14660-16). ISBN

9790004335611. 10 x 12.5

inches. All

conducting scores and

orchestral parts as well

as piano-vocal scores and

choral parts are thus

obtainable exclusively

from Breitkopf &

Hartel. The piano

reductions of Beethoven's

solo concertos and the

study scores

(,,Studien-Editionen)

remain within the

G. Henle Verlag and

can be ordered there.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Ludwig van

Beethoven komponierte

seine Missa solemnis

zwischen 1819 und 1822.

Die vorliegende

Ausgabe legt als

Hauptquelle die

Arbeitskopie der Partitur

zugrunde die Beethoven

wohl unmittelbar nach

Fertigstellung der

Komposition in Auftrag

gab. Sie ist die alteste

Abschrift des Werks und

die einzige Kopie die das

heute unvollstandige

Autograph zur Vorlage

hatte. Da die

Arbeitskopie im Zuge des

weiteren Kopierens immer

wieder selbst revidiert

und korrigiert wurde

kommt sie heute einer

Fassung letzter Hand am

nachsten. Alle

Dirigierpartituren und

Orchesterstimmen sind

exklusiv uber Breitkopf

& Hartel erhaltlich.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Beethov

ens komplexe

Veroffentlichungsstrategi

e einer gleichzeitigen

Herausgabe in England

Frankreich und

Deutschland bei der er

nach der grosstmoglichen

Verbreitung seiner Werke

trachtete wirft die

schwierige Frage nach der

richtigen Datierung der

Originalausgabe auf.

So konnte

Hans-Werner Kuthen bei

seiner Urtextausgabe der

Ouverture zu Coriolan

nachweisen dass es sich

bei der ursprunglich als

authentisch bewerteten

Quelle vom 1. September

1807 doch um einen

Nachdruck Simrocks

handelt den Beethoven in

einem Brief vom 16. Juni

1807 offensichtlich als

ein toleriertes Relikt

erwahnt. Verbindlich fur

die Neuausgabe ist allein

der Wiener Originaldruck

des Industriekontors der

vor der Simrock-Ausgabe

entstanden sein muss. Die

Neubewertung der Quellen

brachte schliesslich auch

Anderungen in der

Artikulation mit sich.

$7.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| Choral Fantasia in C minor Op. 80

Breitkopf & Härtel

Violin 1 (solo: pno - choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. - 2.2.0.0. - timp - str) SKU: BR...(+)

Violin 1 (solo: pno -

choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. -

2.2.0.0. - timp - str)

SKU:

BR.OB-14660-15

Urtext based on the

new Complete Edition (G.

Henle Verlag).

Composed by Ludwig van

Beethoven. Edited by

Armin Raab. Choir;

stapled.

Orchester-Bibliothek

(Orchestral Library). The

study score

(,,Studien-Edition) is

available at G. Henle

Verlag. Have a look into

EB 10546 and CHB 14660.

Solo concerto; Classical.

Part. 8 pages. Duration

16'. Breitkopf and

Haertel #OB 14660-15.

Published by Breitkopf

and Haertel

(BR.OB-14660-15). ISBN

9790004335604. 10 x 12.5

inches. All

conducting scores and

orchestral parts as well

as piano-vocal scores and

choral parts are thus

obtainable exclusively

from Breitkopf &

Hartel. The piano

reductions of Beethoven's

solo concertos and the

study scores

(,,Studien-Editionen)

remain within the

G. Henle Verlag and

can be ordered there.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Ludwig van

Beethoven komponierte

seine Missa solemnis

zwischen 1819 und 1822.

Die vorliegende

Ausgabe legt als

Hauptquelle die

Arbeitskopie der Partitur

zugrunde die Beethoven

wohl unmittelbar nach

Fertigstellung der

Komposition in Auftrag

gab. Sie ist die alteste

Abschrift des Werks und

die einzige Kopie die das

heute unvollstandige

Autograph zur Vorlage

hatte. Da die

Arbeitskopie im Zuge des

weiteren Kopierens immer

wieder selbst revidiert

und korrigiert wurde

kommt sie heute einer

Fassung letzter Hand am

nachsten. Alle

Dirigierpartituren und

Orchesterstimmen sind

exklusiv uber Breitkopf

& Hartel erhaltlich.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Beethov

ens komplexe

Veroffentlichungsstrategi

e einer gleichzeitigen

Herausgabe in England

Frankreich und

Deutschland bei der er

nach der grosstmoglichen

Verbreitung seiner Werke

trachtete wirft die

schwierige Frage nach der

richtigen Datierung der

Originalausgabe auf.

So konnte

Hans-Werner Kuthen bei

seiner Urtextausgabe der

Ouverture zu Coriolan

nachweisen dass es sich

bei der ursprunglich als

authentisch bewerteten

Quelle vom 1. September

1807 doch um einen

Nachdruck Simrocks

handelt den Beethoven in

einem Brief vom 16. Juni

1807 offensichtlich als

ein toleriertes Relikt

erwahnt. Verbindlich fur

die Neuausgabe ist allein

der Wiener Originaldruck

des Industriekontors der

vor der Simrock-Ausgabe

entstanden sein muss. Die

Neubewertung der Quellen

brachte schliesslich auch

Anderungen in der

Artikulation mit sich.

$7.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| Choral Fantasia in C minor Op. 80

Breitkopf & Härtel

Violoncello (solo: pno - choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. - 2.2.0.0. - timp - str) SKU:...(+)

Violoncello (solo: pno -

choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. -

2.2.0.0. - timp - str)

SKU:

BR.OB-14660-23

Urtext based on the

new Complete Edition (G.

Henle Verlag).

Composed by Ludwig van

Beethoven. Edited by

Armin Raab. Choir;

stapled.

Orchester-Bibliothek

(Orchestral Library). The

study score

(,,Studien-Edition) is

available at G. Henle

Verlag. Have a look into

EB 10546 and CHB 14660.

Solo concerto; Classical.

Part. 8 pages. Duration

16'. Breitkopf and

Haertel #OB 14660-23.

Published by Breitkopf

and Haertel

(BR.OB-14660-23). ISBN

9790004335635. 10 x 12.5

inches. All

conducting scores and

orchestral parts as well

as piano-vocal scores and

choral parts are thus

obtainable exclusively

from Breitkopf &

Hartel. The piano

reductions of Beethoven's

solo concertos and the

study scores

(,,Studien-Editionen)

remain within the

G. Henle Verlag and

can be ordered there.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Ludwig van

Beethoven komponierte

seine Missa solemnis

zwischen 1819 und 1822.

Die vorliegende

Ausgabe legt als

Hauptquelle die

Arbeitskopie der Partitur

zugrunde die Beethoven

wohl unmittelbar nach

Fertigstellung der

Komposition in Auftrag

gab. Sie ist die alteste

Abschrift des Werks und

die einzige Kopie die das

heute unvollstandige

Autograph zur Vorlage

hatte. Da die

Arbeitskopie im Zuge des

weiteren Kopierens immer

wieder selbst revidiert

und korrigiert wurde

kommt sie heute einer

Fassung letzter Hand am

nachsten. Alle

Dirigierpartituren und

Orchesterstimmen sind

exklusiv uber Breitkopf

& Hartel erhaltlich.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Beethov

ens komplexe

Veroffentlichungsstrategi

e einer gleichzeitigen

Herausgabe in England

Frankreich und

Deutschland bei der er

nach der grosstmoglichen

Verbreitung seiner Werke

trachtete wirft die

schwierige Frage nach der

richtigen Datierung der

Originalausgabe auf.

So konnte

Hans-Werner Kuthen bei

seiner Urtextausgabe der

Ouverture zu Coriolan

nachweisen dass es sich

bei der ursprunglich als

authentisch bewerteten

Quelle vom 1. September

1807 doch um einen

Nachdruck Simrocks

handelt den Beethoven in

einem Brief vom 16. Juni

1807 offensichtlich als

ein toleriertes Relikt

erwahnt. Verbindlich fur

die Neuausgabe ist allein

der Wiener Originaldruck

des Industriekontors der

vor der Simrock-Ausgabe

entstanden sein muss. Die

Neubewertung der Quellen

brachte schliesslich auch

Anderungen in der

Artikulation mit sich.

$7.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| Choral Fantasia in C minor Op. 80

Breitkopf & Härtel

Viola (solo: pno - choir: SATB - 2.2.2.2. - 2.2.0.0. - timp - str) SKU: BR.OB...(+)

Viola (solo: pno - choir:

SATB - 2.2.2.2. -

2.2.0.0. - timp - str)

SKU:

BR.OB-14660-19

Urtext based on the

new Complete Edition (G.

Henle Verlag).

Composed by Ludwig van

Beethoven. Edited by

Armin Raab. Choir;

stapled.

Orchester-Bibliothek

(Orchestral Library). The

study score

(,,Studien-Edition) is

available at G. Henle

Verlag. Have a look into

EB 10546 and CHB 14660.

Solo concerto; Classical.

Part. 8 pages. Duration

16'. Breitkopf and

Haertel #OB 14660-19.

Published by Breitkopf

and Haertel

(BR.OB-14660-19). ISBN

9790004335628. 10 x 12.5

inches. All

conducting scores and

orchestral parts as well

as piano-vocal scores and

choral parts are thus

obtainable exclusively

from Breitkopf &

Hartel. The piano

reductions of Beethoven's

solo concertos and the

study scores

(,,Studien-Editionen)

remain within the

G. Henle Verlag and

can be ordered there.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Ludwig van

Beethoven komponierte

seine Missa solemnis

zwischen 1819 und 1822.

Die vorliegende

Ausgabe legt als

Hauptquelle die

Arbeitskopie der Partitur

zugrunde die Beethoven

wohl unmittelbar nach

Fertigstellung der

Komposition in Auftrag

gab. Sie ist die alteste

Abschrift des Werks und

die einzige Kopie die das

heute unvollstandige

Autograph zur Vorlage

hatte. Da die

Arbeitskopie im Zuge des

weiteren Kopierens immer

wieder selbst revidiert

und korrigiert wurde

kommt sie heute einer

Fassung letzter Hand am

nachsten. Alle

Dirigierpartituren und

Orchesterstimmen sind

exklusiv uber Breitkopf

& Hartel erhaltlich.

Die Studien-Editionen

(Studienpartituren)

verbleiben beim

G. Henle Verlag und

sind dort erhaltlich.

Beethov

ens komplexe

Veroffentlichungsstrategi

e einer gleichzeitigen

Herausgabe in England

Frankreich und

Deutschland bei der er

nach der grosstmoglichen

Verbreitung seiner Werke

trachtete wirft die

schwierige Frage nach der

richtigen Datierung der

Originalausgabe auf.

So konnte

Hans-Werner Kuthen bei

seiner Urtextausgabe der

Ouverture zu Coriolan

nachweisen dass es sich

bei der ursprunglich als

authentisch bewerteten

Quelle vom 1. September

1807 doch um einen

Nachdruck Simrocks

handelt den Beethoven in

einem Brief vom 16. Juni

1807 offensichtlich als

ein toleriertes Relikt

erwahnt. Verbindlich fur

die Neuausgabe ist allein

der Wiener Originaldruck

des Industriekontors der

vor der Simrock-Ausgabe

entstanden sein muss. Die

Neubewertung der Quellen

brachte schliesslich auch

Anderungen in der

Artikulation mit sich.

$7.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| COMPLETE MANDOLINIST, VOLUME 2: MUSIC IN CONTEXT

Mandoline - Intermédiaire/avancé

Mel Bay

Perfect binding. Exercises. Book. Mel Bay Publications, Inc #30782. Publishe...(+)

Perfect binding.

Exercises.

Book. Mel Bay

Publications,

Inc #30782. Published by

Mel

Bay Publications, Inc

$34.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Taiwan Fantasia for Brass Quintet

Quintette de Cuivres: 2 trompettes, Cor, trombone, tuba [Conducteur et Parties séparées] - Avancé

Cherry Classics

Brass Quintet - Advanced SKU: CY.CC3020 Composed by John van Deursen. Arr...(+)

Brass Quintet - Advanced

SKU: CY.CC3020

Composed by John van

Deursen. Arranged by John

van Deursen. Classical.

Score and Parts. Cherry

Classics #CC3020.

Published by Cherry

Classics (CY.CC3020).

ISBN 9781774310601.

8.5 x 11 in

inches. About the

Taiwan Fantasia, van

Deursen states: After

having lived in Taipei

for a number of years, I

learned many of the local

folk and popular songs.

Some of the melodies are

exceptionally beautiful,

and my idea was to

somehow combine all the

elements that have made

up my musical experiences

over these years -

Chinese melodies, western

orchestral music and

jazz; I wanted to see if

these songs could survive

with a totally different

harmonic structure and

concept. My original goal

was to write a simple

arrangement of the two

songs, but quickly I

discovered more melodies

building upon the

original ones and thus

the Variations were born.

Composed in 1995, this

work of about 10 minutes

in length is in one

continuous movement, but

is divided into seven

short sections of

contrasting moods

including two cadenzas,

for Trumpet and Trombone.

The music is appropriate

for advanced performers.

Parts in C and B-flat are

supplied for the

Trumpets. A recording of

Taiwan Fantasia can be

purchased on iTunes from

the album by the Yeh Shu

Han Brass Quintet. $37.50 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

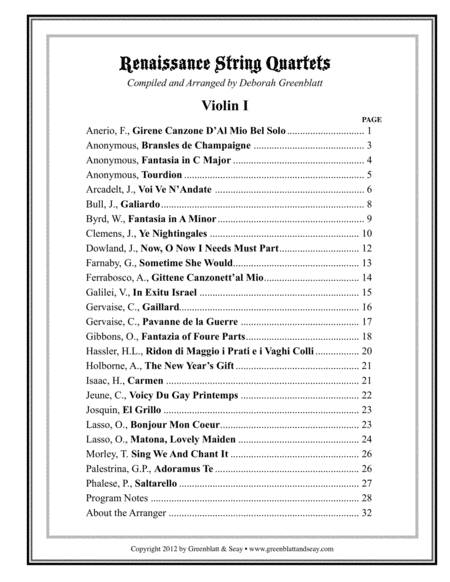

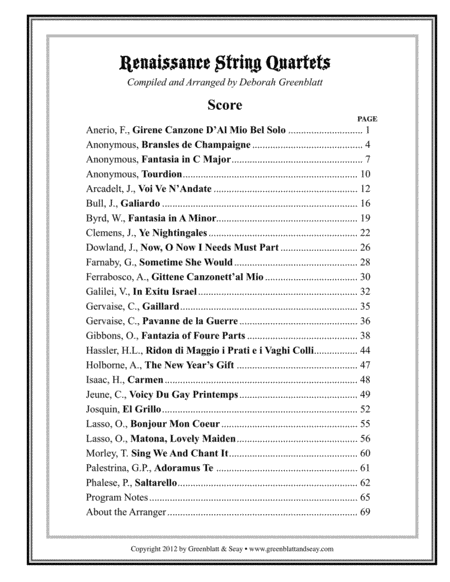

| Renaissance String Quartets - Parts

Quatuor à cordes: 2 violons, alto, violoncelle

Greenblatt and Seay

Arranged by Deborah Greenblatt. String Quartet. For violin 1, violin 2, viola, c...(+)

Arranged by Deborah

Greenblatt. String

Quartet. For violin 1,

violin 2, viola, cello.

This edition:

spiral-bound. Tunebook.

26 pages (violin 1), 26

pages (violin 2), 26

pages (viola), 26 pages

(cello). Published by

Greenblatt & Seay

$30.00 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| Twelve Fantasias

Kevin Mayhew

These twelve fantasias by Telemann for unaccompanied flute (composed around 1728...(+)

These twelve fantasias by

Telemann for

unaccompanied flute

(composed around 1728)

hold much for modern

flute players to discover

and enjoy. Telemann's

flute compositions had

universal appeal, being

enjoyable for the less

dexterous players while

remaining attractive to

virtuosi. He embraced

multiple styles and

forms, creating simple

yet effective works which

are relatively easy to

master but also highly

satisfying. This edition

includes a complete

performance on CD

$21.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| Renaissance String Quartets - Score

Quatuor à cordes: 2 violons, alto, violoncelle [Conducteur]

Greenblatt and Seay

Arranged by Deborah Greenblatt. String Quartet. For violin 1, violin 2, viola, c...(+)

Arranged by Deborah

Greenblatt. String

Quartet. For violin 1,

violin 2, viola, cello.

This edition:

spiral-bound. Tunebook.

63 pages. Published by

Greenblatt & Seay

$15.00 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| Organ Works, Volume 6

Orgue [Conducteur]

Barenreiter

Preludes, Toccatas, Fantasias and Fugues II / Early Versions and Variants to ...(+)

Preludes, Toccatas,

Fantasias and Fugues II /

Early Versions and

Variants to I (Volume 5)

and II (Volume 6).

Composed by Johann

Sebastian Bach

(1685-1750). Edited by

Dietrich Kilian / Peter

Wollny. This edition:

urtext edition.

Paperback. Johann

Sebastian Bach. Organ

Works 6 | BARENREITER

URTEXT. Preludes,

Toccatas, Fantasias and

Fugues II / Early

Versions and Variants to

I (Volume 5) and II

(Volume 6). Performance

score, anthology.

Published by Baerenreiter

Verlag (BA.BA5266).

$38.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| The Organ Wedding Album

Orgue

Barenreiter

(Easy Organ Music for Grand Occasions) Edited by Martin Bartsch. For organ. Form...(+)

(Easy Organ Music for

Grand Occasions) Edited

by Martin Bartsch. For

organ. Format: organ solo

book. With organ notation

and introductory text.

Wedding. 82 pages. 9x12

inches. Published by

Baerenreiter-Ausgaben

$46.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| The Classical Piano Solos Collection

Piano seul

Willis Music

106 Graded Pieces from Baroque to the 20th C. Compiled and Edited by P. Low, ...(+)

106 Graded Pieces from

Baroque to the 20th C.

Compiled and Edited by P.

Low,

S. Schumann, C. Siagian.

Composed by Various.

Edited

by Charmaine Siagian.

Willis.

Classical, Recital,

Solos.

Softcover. Published by

Willis Music

$27.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| English Consort Music

Flûte à bec Soprano [Partition + Accès audio]

Music Minus One

Music Minus One Recorder. Composed by Various. Sheet music with CD. Music Minus ...(+)

Music Minus One Recorder.

Composed by Various.

Sheet music with CD.

Music Minus One.

Classical. Softcover

Audio Online. 56 pages.

Music Minus One #MMO3359.

Published by Music Minus

One

(1)$16.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Essential Keyboard Repertoire, Volume 8 (Miniatures)

Piano seul [Partition] - Facile

Alfred Publishing

95 Early / Late Intermediate Miniatures - Baroque to Modern. Edited by Maurice H...(+)

95 Early / Late

Intermediate Miniatures -

Baroque to Modern. Edited

by Maurice Hinson. For

Piano. Piano Collection.

Essential Keyboard

Repertoire. Masterwork.

Level: Early Intermediate

/ Late Intermediate.

Book. 144 pages.

Published by Alfred

Publishing. (

$17.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| RIMSKY-KORSAKOV Concerto in C-sharp minor, op. 30; ARENSKY Fantasia on Russian Folksongs, op. 48 (2 CD set)

Piano et Orchestre [Partition + CD] - Intermédiaire

Music Minus One

For Piano. Includes a printed music score on high-quality ivory paper; a digital...(+)

For Piano. Includes a

printed music score on

high-quality ivory paper;

a digital stereo compact

disc featuring a complete

performance of the

concerto with orchestra

and soloist, and a second

performance minus you,

the soloist; and a second

compact disc containing a

full-speed version of the

complete version as well

as a special -20%

slow-tempo version of the

accompaniment for

practice purposes. Each

concerto is voluminously

indexed for your practice

and performance

convenience. Published by

Music Minus One.

(1)$19.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Fantasia D 934

Violon et Piano [Conducteur et Parties séparées] - Intermédiaire

Barenreiter

Urtext der Neuen Schubert-Ausgabe. By Franz Schubert. Edited by Wirth, Helmut. F...(+)

Urtext der Neuen

Schubert-Ausgabe. By

Franz Schubert. Edited by

Wirth, Helmut. For

Violin, Piano. Playing

Score; Single Part;

Urtext Edition

(paperbound).

Op.post.159. Published by

Baerenreiter-Ausgaben

(German import).

$22.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | |

|