|

| The Best Fake Book Ever - 2nd Edition - Eb Edition

Instruments en Mib [Fake Book]

Hal Leonard

Fakebook for Eb instrument. With vocal melody, lyrics and chord names. Series: H...(+)

Fakebook for Eb

instrument. With vocal

melody, lyrics and chord

names. Series: Hal

Leonard Fake Books. 864

pages. Published by Hal

Leonard.

(2)$49.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Best Fake Book Ever - 5th Edition

Instruments en Do [Fake Book]

Hal Leonard

C Edition. Composed by Various. Fake Book. Broadway, Country, Jazz, Pop, Stand...(+)

C Edition. Composed by

Various. Fake Book.

Broadway,

Country, Jazz, Pop,

Standards.

Softcover. 802 pages.

Published by Hal Leonard

$49.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| The Best Fake Book Ever - C Edition - 3rd Edition

Fake Book [Fake Book]

Hal Leonard

(C Edition) For voice and C instrument. Format: fakebook. With vocal melody, lyr...(+)

(C Edition) For voice and

C instrument. Format:

fakebook. With vocal

melody, lyrics and chord

names. Series: Hal

Leonard Fake Books. 856

pages. 9x12 inches.

Published by Hal Leonard.

(14)$59.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Buskers Fake Book All Time Hit

Piano seul

Music Sales

| | | |

| Fake Book Of The World's Favorite Songs - C Instruments - 4th Edition

Instruments en Do [Fake Book]

Hal Leonard

For voice and C instrument. Format: fakebook. With vocal melody, lyrics and chor...(+)

For voice and C

instrument. Format:

fakebook. With vocal

melody, lyrics and chord

names. Traditional pop

and vocal standards.

Series: Hal Leonard Fake

Books. 424 pages. 9x12

inches. Published by Hal

Leonard.

(14)$34.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

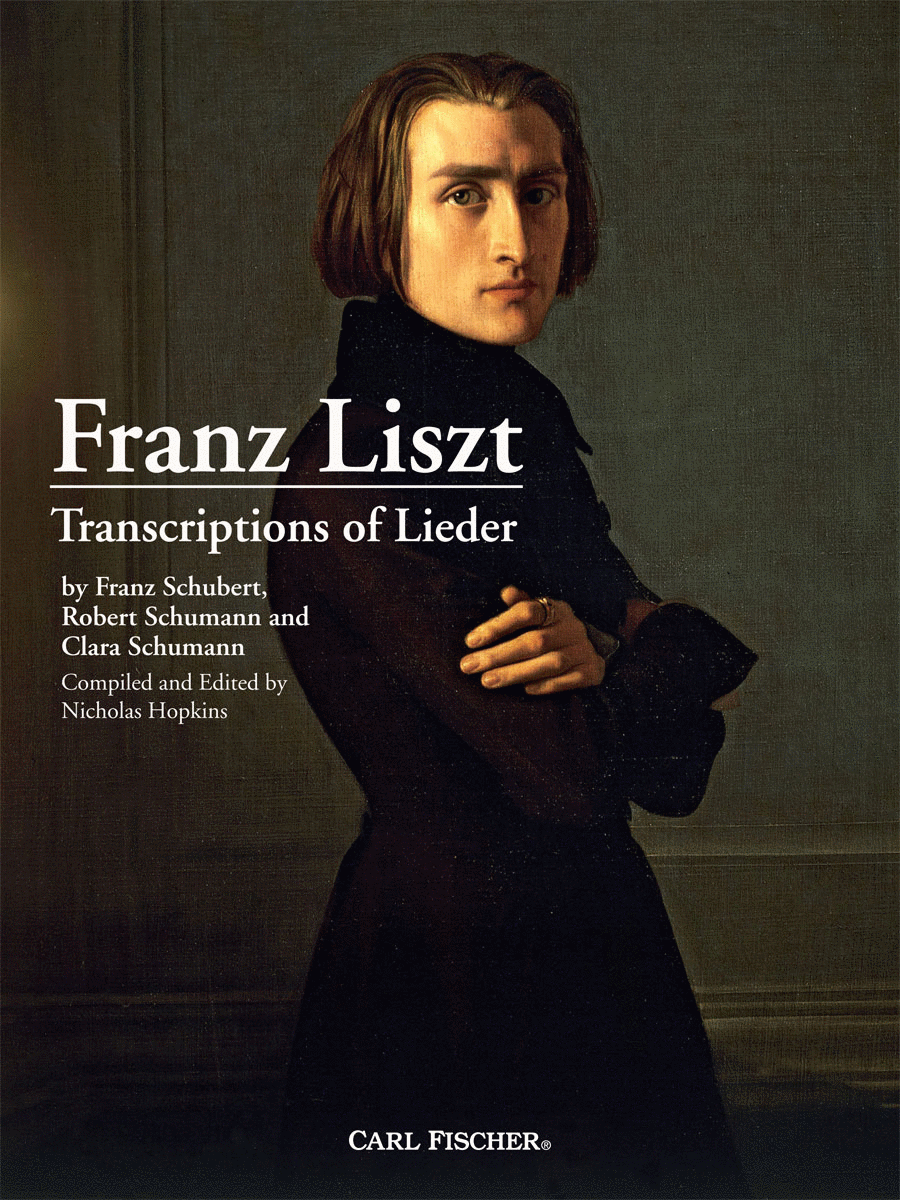

| Transcriptions of Lieder

Piano seul

Carl Fischer

Chamber Music Piano SKU: CF.PL1056 Composed by Clara Wieck-Schumann, Fran...(+)

Chamber Music Piano

SKU: CF.PL1056

Composed by Clara

Wieck-Schumann, Franz

Schubert, and Robert

Schumann. Edited by

Nicholas Hopkins.

Collection. With Standard

notation. 128 pages. Carl

Fischer Music #PL1056.

Published by Carl Fischer

Music (CF.PL1056).

ISBN 9781491153390.

UPC: 680160910892.

Transcribed by Franz

Liszt. Introduction

It is true that Schubert

himself is somewhat to

blame for the very

unsatisfactory manner in

which his admirable piano

pieces are treated. He

was too immoderately

productive, wrote

incessantly, mixing

insignificant with

important things, grand

things with mediocre

work, paid no heed to

criticism, and always

soared on his wings. Like

a bird in the air, he

lived in music and sang

in angelic fashion.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Dr. S. Lebert (1868) Of

those compositions that

greatly interest me,

there are only Chopin's

and yours. --Franz Liszt,

letter to Robert Schumann

(1838) She [Clara

Schumann] was astounded

at hearing me. Her

compositions are really

very remarkable,

especially for a woman.

There is a hundred times

more creativity and real

feeling in them than in

all the past and present

fantasias by Thalberg.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Marie d'Agoult (1838)

Chretien Urhan

(1790-1845) was a

Belgian-born violinist,

organist and composer who

flourished in the musical

life of Paris in the

early nineteenth century.

According to various

accounts, he was deeply

religious, harshly

ascetic and wildly

eccentric, though revered

by many important and

influential members of

the Parisian musical

community. Regrettably,

history has forgotten

Urhan's many musical

achievements, the most

important of which was

arguably his pioneering

work in promoting the

music of Franz Schubert.

He devoted much of his

energies to championing

Schubert's music, which

at the time was unknown

outside of Vienna.

Undoubtedly, Urhan was

responsible for

stimulating this

enthusiasm in Franz

Liszt; Liszt regularly

heard Urhan's organ

playing in the

St.-Vincent-de-Paul

church in Paris, and the

two became personal

acquaintances. At

eighteen years of age,

Liszt was on the verge of

establishing himself as

the foremost pianist in

Europe, and this

awakening to Schubert's

music would prove to be a

profound experience.

Liszt's first travels

outside of his native

provincial Hungary were

to Vienna in 1821-1823,

where his father enrolled

him in studies with Carl

Czerny (piano) and

Antonio Salieri (music

theory). Both men had

important involvements

with Schubert; Czerny

(like Urhan) as performer

and advocate of

Schubert's music and

Salieri as his theory and

composition teacher from

1813-1817. Curiously,

Liszt and Schubert never

met personally, despite

their geographical

proximity in Vienna

during these years.

Inevitably, legends later

arose that the two had

been personal

acquaintances, although

Liszt would dismiss these

as fallacious: I never

knew Schubert personally,

he was once quoted as

saying. Liszt's initial

exposure to Schubert's

music was the Lieder,

what Urhan prized most of

all. He accompanied the

tenor Benedict

Randhartinger in numerous

performances of

Schubert's Lieder and

then, perhaps realizing

that he could benefit the

composer more on his own

terms, transcribed a

number of the Lieder for

piano solo. Many of these

transcriptions he would

perform himself on

concert tour during the

so-called Glanzzeit, or

time of splendor from

1839-1847. This publicity

did much to promote

reception of Schubert's

music throughout Europe.

Once Liszt retired from

the concert stage and

settled in Weimar as a

conductor in the 1840s,

he continued to perform

Schubert's orchestral

music, his Symphony No. 9

being a particular

favorite, and is credited

with giving the world

premiere performance of

Schubert's opera Alfonso

und Estrella in 1854. At

this time, he

contemplated writing a

biography of the

composer, which

regrettably remained

uncompleted. Liszt's

devotion to Schubert

would never waver.

Liszt's relationship with

Robert and Clara Schumann

was far different and far

more complicated; by

contrast, they were all

personal acquaintances.

What began as a

relationship of mutual

respect and admiration

soon deteriorated into

one of jealousy and

hostility, particularly

on the Schumann's part.

Liszt's initial contact

with Robert's music

happened long before they

had met personally, when

Liszt published an

analysis of Schumann's

piano music for the

Gazette musicale in 1837,

a gesture that earned

Robert's deep

appreciation. In the

following year Clara met

Liszt during a concert

tour in Vienna and

presented him with more

of Schumann's piano

music. Clara and her

father Friedrich Wieck,

who accompanied Clara on

her concert tours, were

quite taken by Liszt: We

have heard Liszt. He can

be compared to no other

player...he arouses

fright and astonishment.

His appearance at the

piano is indescribable.

He is an original...he is

absorbed by the piano.

Liszt, too, was impressed

with Clara--at first the

energy, intelligence and

accuracy of her piano

playing and later her

compositions--to the

extent that he dedicated

to her the 1838 version

of his Etudes d'execution

transcendante d'apres

Paganini. Liszt had a

closer personal

relationship with Clara

than with Robert until

the two men finally met

in 1840. Schumann was

astounded by Liszt's

piano playing. He wrote

to Clara that Liszt had

played like a god and had

inspired indescribable

furor of applause. His

review of Liszt even

included a heroic

personification with

Napoleon. In Leipzig,

Schumann was deeply

impressed with Liszt's

interpretations of his

Noveletten, Op. 21 and

Fantasy in C Major, Op.

17 (dedicated to Liszt),

enthusiastically

observing that, I feel as

if I had known you twenty

years. Yet a variety of

events followed that

diminished Liszt's glory

in the eyes of the

Schumanns. They became

critical of the cult-like

atmosphere that arose

around his recitals, or

Lisztomania as it came to

be called; conceivably,

this could be attributed

to professional jealousy.

Clara, in particular,

came to loathe Liszt,

noting in a letter to

Joseph Joachim, I despise

Liszt from the depths of

my soul. She recorded a

stunning diary entry a

day after Liszt's death,

in which she noted, He

was an eminent keyboard

virtuoso, but a dangerous

example for the

young...As a composer he

was terrible. By

contrast, Liszt did not

share in these negative

sentiments; no evidence

suggests that he had any

ill-regard for the

Schumanns. In Weimar, he

did much to promote

Schumann's music,

conducting performances

of his Scenes from Faust

and Manfred, during a

time in which few

orchestras expressed

interest, and premiered

his opera Genoveva. He

later arranged a benefit

concert for Clara

following Robert's death,

featuring Clara as

soloist in Robert's Piano

Concerto, an event that

must have been

exhilarating to witness.

Regardless, her opinion

of him would never

change, despite his

repeated gestures of

courtesy and respect.

Liszt's relationship with

Schubert was a spiritual

one, with music being the

one and only link between

the two men. That with

the Schumanns was

personal, with music

influenced by a hero

worship that would

aggravate the

relationship over time.

Nonetheless, Liszt would

remain devoted to and

enthusiastic for the

music and achievements of

these composers. He would

be a vital force in

disseminating their music

to a wider audience, as

he would be with many

other composers

throughout his career.

His primary means for

accomplishing this was

the piano transcription.

Liszt and the

Transcription

Transcription versus

Paraphrase Transcription

and paraphrase were

popular terms in

nineteenth-century music,

although certainly not

unique to this period.

Musicians understood that

there were clear

distinctions between

these two terms, but as

is often the case these

distinctions could be

blurred. Transcription,

literally writing over,

entails reworking or

adapting a piece of music

for a performance medium

different from that of

its original; arrangement

is a possible synonym.

Adapting is a key part of

this process, for the

success of a

transcription relies on

the transcriber's ability

to adapt the piece to the

different medium. As a

result, the pre-existing

material is generally

kept intact, recognizable

and intelligible; it is

strict, literal,

objective. Contextual

meaning is maintained in

the process, as are

elements of style and

form. Paraphrase, by

contrast, implies

restating something in a

different manner, as in a

rewording of a document

for reasons of clarity.

In nineteenth-century

music, paraphrasing

indicated elaborating a

piece for purposes of

expressive virtuosity,

often as a vehicle for

showmanship. Variation is

an important element, for

the source material may

be varied as much as the

paraphraser's imagination

will allow; its purpose

is metamorphosis.

Transcription is adapting

and arranging;

paraphrasing is

transforming and

reworking. Transcription

preserves the style of

the original; paraphrase

absorbs the original into

a different style.

Transcription highlights

the original composer;

paraphrase highlights the

paraphraser.

Approximately half of

Liszt's compositional

output falls under the

category of transcription

and paraphrase; it is

noteworthy that he never

used the term

arrangement. Much of his

early compositional

activities were

transcriptions and

paraphrases of works of

other composers, such as

the symphonies of

Beethoven and Berlioz,

vocal music by Schubert,

and operas by Donizetti

and Bellini. It is

conceivable that he

focused so intently on

work of this nature early

in his career as a means

to perfect his

compositional technique,

although transcription

and paraphrase continued

well after the technique

had been mastered; this

might explain why he

drastically revised and

rewrote many of his

original compositions

from the 1830s (such as

the Transcendental Etudes

and Paganini Etudes) in

the 1850s. Charles Rosen,

a sympathetic interpreter

of Liszt's piano works,

observes, The new

revisions of the

Transcendental Etudes are

not revisions but concert

paraphrases of the old,

and their art lies in the

technique of

transformation. The

Paganini etudes are piano

transcriptions of violin

etudes, and the

Transcendental Etudes are

piano transcriptions of

piano etudes. The

principles are the same.

He concludes by noting,

Paraphrase has shaded off

into

composition...Composition

and paraphrase were not

identical for him, but

they were so closely

interwoven that

separation is impossible.

The significance of

transcription and

paraphrase for Liszt the

composer cannot be

overstated, and the

mutual influence of each

needs to be better

understood. Undoubtedly,

Liszt the composer as we

know him today would be

far different had he not

devoted so much of his

career to transcribing

and paraphrasing the

music of others. He was

perhaps one of the first

composers to contend that

transcription and

paraphrase could be

genuine art forms on

equal par with original

pieces; he even claimed

to be the first to use

these two terms to

describe these classes of

arrangements. Despite the

success that Liszt

achieved with this type

of work, others viewed it

with circumspection and

criticism. Robert

Schumann, although deeply

impressed with Liszt's

keyboard virtuosity, was

harsh in his criticisms

of the transcriptions.

Schumann interpreted them

as indicators that

Liszt's virtuosity had

hindered his

compositional development

and suggested that Liszt

transcribed the music of

others to compensate for

his own compositional

deficiencies.

Nonetheless, Liszt's

piano transcriptions,

what he sometimes called

partitions de piano (or

piano scores), were

instrumental in promoting

composers whose music was

unknown at the time or

inaccessible in areas

outside of major European

capitals, areas that

Liszt willingly toured

during his Glanzzeit. To

this end, the

transcriptions had to be

literal arrangements for

the piano; a Beethoven

symphony could not be

introduced to an

unknowing audience if its

music had been subjected

to imaginative

elaborations and

variations. The same

would be true of the 1833

transcription of

Berlioz's Symphonie

fantastique (composed

only three years

earlier), the

astonishingly novel

content of which would

necessitate a literal and

intelligible rendering.

Opera, usually more

popular and accessible

for the general public,

was a different matter,

and in this realm Liszt

could paraphrase the

original and manipulate

it as his imagination

would allow without

jeopardizing its

reception; hence, the

paraphrases on the operas

of Bellini, Donizetti,

Mozart, Meyerbeer and

Verdi. Reminiscence was

another term coined by

Liszt for the opera

paraphrases, as if the

composer were reminiscing

at the keyboard following

a memorable evening at

the opera. Illustration

(reserved on two

occasions for Meyerbeer)

and fantasy were

additional terms. The

operas of Wagner were

exceptions. His music was

less suited to paraphrase

due to its general lack

of familiarity at the

time. Transcription of

Wagner's music was thus

obligatory, as it was of

Beethoven's and Berlioz's

music; perhaps the

composer himself insisted

on this approach. Liszt's

Lieder Transcriptions

Liszt's initial

encounters with

Schubert's music, as

mentioned previously,

were with the Lieder. His

first transcription of a

Schubert Lied was Die

Rose in 1833, followed by

Lob der Tranen in 1837.

Thirty-nine additional

transcriptions appeared

at a rapid pace over the

following three years,

and in 1846, the Schubert

Lieder transcriptions

would conclude, by which

point he had completed

fifty-eight, the most of

any composer. Critical

response to these

transcriptions was highly

favorable--aside from the

view held by

Schumann--particularly

when Liszt himself played

these pieces in concert.

Some were published

immediately by Anton

Diabelli, famous for the

theme that inspired

Beethoven's variations.

Others were published by

the Viennese publisher

Tobias Haslinger (one of

Beethoven's and

Schubert's publishers in

the 1820s), who sold his

reserves so quickly that

he would repeatedly plead

for more. However,

Liszt's enthusiasm for

work of this nature soon

became exhausted, as he

noted in a letter of 1839

to the publisher

Breitkopf und Hartel:

That good Haslinger

overwhelms me with

Schubert. I have just

sent him twenty-four new

songs (Schwanengesang and

Winterreise), and for the

moment I am rather tired

of this work. Haslinger

was justified in his

demands, for the Schubert

transcriptions were

received with great

enthusiasm. One Gottfried

Wilhelm Fink, then editor

of the Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung,

observed of these

transcriptions: Nothing

in recent memory has

caused such sensation and

enjoyment in both

pianists and audiences as

these arrangements...The

demand for them has in no

way been satisfied; and

it will not be until

these arrangements are

seen on pianos

everywhere. They have

indeed made quite a

splash. Eduard Hanslick,

never a sympathetic

critic of Liszt's music,

acknowledged thirty years

after the fact that,

Liszt's transcriptions of

Schubert Lieder were

epoch-making. There was

hardly a concert in which

Liszt did not have to

play one or two of

them--even when they were

not listed on the

program. These

transcriptions quickly

became some of his most

sough-after pieces,

despite their extreme

technical demands.

Leading pianists of the

day, such as Clara Wieck

and Sigismond Thalberg,

incorporated them into

their concert programs

immediately upon

publication. Moreover,

the transcriptions would

serve as inspirations for

other composers, such as

Stephen Heller, Cesar

Franck and later Leopold

Godowsky, all of whom

produced their own

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder. Liszt

would transcribe the

Lieder of other composers

as well, including those

by Mendelssohn, Chopin,

Anton Rubinstein and even

himself. Robert Schumann,

of course, would not be

ignored. The first

transcription of a

Schumann Lied was the

celebrated Widmung from

Myrten in 1848, the only

Schumann transcription

that Liszt completed

during the composer's

lifetime. (Regrettably,

there is no evidence of

Schumann's regard of this

transcription, or even if

he was aware of it.) From

the years 1848-1881,

Liszt transcribed twelve

of Robert Schumann's

Lieder (including one

orchestral Lied) and

three of Clara (one from

each of her three

published Lieder cycles);

he would transcribe no

other works of these two

composers. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions,

contrary to those of

Schubert, are literal

arrangements, posing, in

general, far fewer

demands on the pianist's

technique. They are

comparatively less

imaginative in their

treatment of the original

material. Additionally,

they seem to have been

less valued in their day

than the Schubert

transcriptions, and it is

noteworthy that none of

the Schumann

transcriptions bear

dedications, as most of

the Schubert

transcriptions do. The

greatest challenge posed

by Lieder transcriptions,

regardless of the

composer or the nature of

the transcription, was to

combine the vocal and

piano parts of the

original such that the

character of each would

be preserved, a challenge

unique to this form of

transcription. Each part

had to be intact and

aurally recognizable, the

vocal line in particular.

Complications could be

manifold in a Lied that

featured dissimilar

parts, such as Schubert's

Auf dem Wasser zu singen,

whose piano accompaniment

depicts the rocking of

the boat on the

shimmering waves while

the vocal line reflects

on the passing of time.

Similar complications

would be encountered in

Gretchen am Spinnrade, in

which the ubiquitous

sixteenth-note pattern in

the piano's right hand

epitomizes the

ever-turning spinning

wheel over which the

soprano voice expresses

feelings of longing and

heartache. The resulting

transcriptions for solo

piano would place

exceptional demands on

the pianist. The

complications would be

far less imposing in

instances in which voice

and piano were less

differentiated, as in

many of Schumann's Lieder

that Liszt transcribed.

The piano parts in these

Lieder are true

accompaniments for the

voice, providing harmonic

foundation and rhythmic

support by doubling the

vocal line throughout.

The transcriptions, thus,

are strict and literal,

with far fewer demands on

both pianist and

transcriber. In all of

Liszt's Lieder

transcriptions,

regardless of the way in

which the two parts are

combined, the melody

(i.e. the vocal line) is

invariably the focal

point; the melody should

sing on the piano, as if

it were the voice. The

piano part, although

integral to contributing

to the character of the

music, is designed to

function as

accompaniment. A singing

melody was a crucial

objective in

nineteenth-century piano

performance, which in

part might explain the

zeal in transcribing and

paraphrasing vocal music

for the piano. Friedrich

Wieck, father and teacher

of Clara Schumann,

stressed this point

repeatedly in his 1853

treatise Clavier und

Gesang (Piano and Song):

When I speak in general

of singing, I refer to

that species of singing

which is a form of

beauty, and which is a

foundation for the most

refined and most perfect

interpretation of music;

and, above all things, I

consider the culture of

beautiful tones the basis

for the finest possible

touch on the piano. In

many respects, the piano

and singing should

explain and supplement

each other. They should

mutually assist in

expressing the sublime

and the noble, in forms

of unclouded beauty. Much

of Liszt's piano music

should be interpreted

with this concept in

mind, the Lieder

transcriptions and opera

paraphrases, in

particular. To this end,

Liszt provided numerous

written instructions to

the performer to

emphasize the vocal line

in performance, with

Italian directives such

as un poco marcato il

canto, accentuato assai

il canto and ben

pronunziato il canto.

Repeated indications of

cantando,singend and

espressivo il canto

stress the significance

of the singing tone. As

an additional means of

achieving this and

providing the performer

with access to the

poetry, Liszt insisted,

at what must have been a

publishing novelty at the

time, on printing the

words of the Lied in the

music itself. Haslinger,

seemingly oblivious to

Liszt's intent, initially

printed the poems of the

early Schubert

transcriptions separately

inside the front covers.

Liszt argued that the

transcriptions must be

reprinted with the words

underlying the notes,

exactly as Schubert had

done, a request that was

honored by printing the

words above the

right-hand staff. Liszt

also incorporated a

visual scheme for

distinguishing voice and

accompaniment, influenced

perhaps by Chopin, by

notating the

accompaniment in cue

size. His transcription

of Robert Schumann's

Fruhlings Ankunft

features the vocal line

in normal size, the piano

accompaniment in reduced

size, an unmistakable

guide in a busy texture

as to which part should

be emphasized: Example 1.

Schumann-Liszt Fruhlings

Ankunft, mm. 1-2. The

same practice may be

found in the

transcription of

Schumann's An die Turen

will ich schleichen. In

this piece, the performer

must read three staves,

in which the baritone

line in the central staff

is to be shared between

the two hands based on

the stem direction of the

notes: Example 2.

Schumann-Liszt An die

Turen will ich

schleichen, mm. 1-5. This

notational practice is

extremely beneficial in

this instance, given the

challenge of reading

three staves and the

manner in which the vocal

line is performed by the

two hands. Curiously,

Liszt did not use this

practice in other

transcriptions.

Approaches in Lieder

Transcription Liszt

adopted a variety of

approaches in his Lieder

transcriptions, based on

the nature of the source

material, the ways in

which the vocal and piano

parts could be combined

and the ways in which the

vocal part could sing.

One approach, common with

strophic Lieder, in which

the vocal line would be

identical in each verse,

was to vary the register

of the vocal part. The

transcription of Lob der

Tranen, for example,

incorporates three of the

four verses of the

original Lied, with the

register of the vocal

line ascending one octave

with each verse (from low

to high), as if three

different voices were

participating. By the

conclusion, the music

encompasses the entire

range of Liszt's keyboard

to produce a stunning

climactic effect, and the

variety of register of

the vocal line provides a

welcome textural variety

in the absence of the

words. The three verses

of the transcription of

Auf dem Wasser zu singen

follow the same approach,

in which the vocal line

ascends from the tenor,

to the alto and to the

soprano registers with

each verse.

Fruhlingsglaube adopts

the opposite approach, in

which the vocal line

descends from soprano in

verse 1 to tenor in verse

2, with the second part

of verse 2 again resuming

the soprano register;

this is also the case in

Das Wandern from

Mullerlieder. Gretchen am

Spinnrade posed a unique

problem. Since the poem's

narrator is female, and

the poem represents an

expression of her longing

for her lover Faust,

variation of the vocal

line's register, strictly

speaking, would have been

impractical. For this

reason, the vocal line

remains in its original

register throughout,

relentlessly colliding

with the sixteenth-note

pattern of the

accompaniment. One

exception may be found in

the fifth and final verse

in mm. 93-112, at which

point the vocal line is

notated in a higher

register and doubled in

octaves. This sudden

textural change, one that

is readily audible, was a

strategic means to

underscore Gretchen's

mounting anxiety (My

bosom urges itself toward

him. Ah, might I grasp

and hold him! And kiss

him as I would wish, at

his kisses I should

die!). The transcription,

thus, becomes a vehicle

for maximizing the

emotional content of the

poem, an exceptional

undertaking with the

general intent of a

transcription. Registral

variation of the vocal

part also plays a crucial

role in the transcription

of Erlkonig. Goethe's

poem depicts the death of

a child who is

apprehended by a

supernatural Erlking, and

Schubert, recognizing the

dramatic nature of the

poem, carefully depicted

the characters (father,

son and Erlking) through

unique vocal writing and

accompaniment patterns:

the Lied is a dramatic

entity. Liszt, in turn,

followed Schubert's

characterization in this

literal transcription,

yet took it an additional

step by placing the

register of the father's

vocal line in the

baritone range, that of

the son in the soprano

range and that of the

Erlking in the highest

register, options that

would not have been

available in the version

for voice and piano.

Additionally, Liszt

labeled each appearance

of each character in the

score, a means for

guiding the performer in

interpreting the dramatic

qualities of the Lied. As

a result, the drama and

energy of the poem are

enhanced in this

transcription; as with

Gretchen am Spinnrade,

the transcriber has

maximized the content of

the original. Elaboration

may be found in certain

Lieder transcriptions

that expand the

performance to a level of

virtuosity not found in

the original; in such

cases, the transcription

approximates the

paraphrase. Schubert's Du

bist die Ruh, a paradigm

of musical simplicity,

features an uncomplicated

piano accompaniment that

is virtually identical in

each verse. In Liszt's

transcription, the

material is subjected to

a highly virtuosic

treatment that far

exceeds the original,

including a demanding

passage for the left hand

alone in the opening

measures and unique

textural writing in each

verse. The piece is a

transcription in

virtuosity; its art, as

Rosen noted, lies in the

technique of

transformation.

Elaboration may entail an

expansion of the musical

form, as in the extensive

introduction to Die

Forelle and a virtuosic

middle section (mm.

63-85), both of which are

not in the original. Also

unique to this

transcription are two

cadenzas that Liszt

composed in response to

the poetic content. The

first, in m. 93 on the

words und eh ich es

gedacht (and before I

could guess it), features

a twisted chromatic

passage that prolongs and

thereby heightens the

listener's suspense as to

the fate of the trout

(which is ultimately

caught). The second, in

m. 108 on the words

Betrogne an (and my blood

boiled as I saw the

betrayed one), features a

rush of

diminished-seventh

arpeggios in both hands,

epitomizing the poet's

rage at the fisherman for

catching the trout. Less

frequent are instances in

which the length of the

original Lied was

shortened in the

transcription, a tendency

that may be found with

certain strophic Lieder

(e.g., Der Leiermann,

Wasserflut and Das

Wandern). Another

transcription that

demonstrates Liszt's

readiness to modify the

original in the interests

of the poetic content is

Standchen, the seventh

transcription from

Schubert's

Schwanengesang. Adapted

from Act II of

Shakespeare's Cymbeline,

the poem represents the

repeated beckoning of a

man to his lover. Liszt

transformed the Lied into

a miniature drama by

transcribing the vocal

line of the first verse

in the soprano register,

that of the second verse

in the baritone register,

in effect, creating a

dialogue between the two

lovers. In mm. 71-102,

the dialogue becomes a

canon, with one voice

trailing the other like

an echo (as labeled in

the score) at the

distance of a beat. As in

other instances, the

transcription resembles

the paraphrase, and it is

perhaps for this reason

that Liszt provided an

ossia version that is

more in the nature of a

literal transcription.

The ossia version, six

measures shorter than

Schubert's original, is

less demanding

technically than the

original transcription,

thus representing an

ossia of transcription

and an ossia of piano

technique. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions, in

general, display a less

imaginative treatment of

the source material.

Elaborations are less

frequently encountered,

and virtuosity is more

restricted, as if the

passage of time had

somewhat tamed the

composer's approach to

transcriptions;

alternatively, Liszt was

eager to distance himself

from the fierce

virtuosity of his early

years. In most instances,

these transcriptions are

literal arrangements of

the source material, with

the vocal line in its

original form combined

with the accompaniment,

which often doubles the

vocal line in the

original Lied. Widmung,

the first of the Schumann

transcriptions, is one

exception in the way it

recalls the virtuosity of

the Schubert

transcriptions of the

1830s. Particularly

striking is the closing

section (mm. 58-73), in

which material of the

opening verse (right

hand) is combined with

the triplet quarter notes

(left hand) from the

second section of the

Lied (mm. 32-43), as if

the transcriber were

attempting to reconcile

the different material of

these two sections.

Fruhlingsnacht resembles

a paraphrase by

presenting each of the

two verses in differing

registers (alto for verse

1, mm. 3-19, and soprano

for verse 2, mm. 20-31)

and by concluding with a

virtuosic section that

considerably extends the

length of the original

Lied. The original

tonalities of the Lieder

were generally retained

in the transcriptions,

showing that the tonality

was an important part of

the transcription

process. The infrequent

instances of

transposition were done

for specific reasons. In

1861, Liszt transcribed

two of Schumann's Lieder,

one from Op. 36 (An den

Sonnenschein), another

from Op. 27 (Dem roten

Roslein), and merged

these two pieces in the

collection 2 Lieder; they

share only the common

tonality of A major. His

choice for combining

these two Lieder remains

unknown, but he clearly

recognized that some

tonal variety would be

needed, for which reason

Dem roten Roslein was

transposed to C>= major.

The collection features

An den Sonnenschein in A

major (with a transition

to the new tonality),

followed by Dem roten

Roslein in C>= major

(without a change of key

signature), and

concluding with a reprise

of An den Sonnenschein in

A major. A three-part

form was thus established

with tonal variety

provided by keys in third

relations (A-C>=-A); in

effect, two of Schumann's

Lieder were transcribed

into an archetypal song

without words. In other

instances, Liszt treated

tonality and tonal

organization as important

structural ingredients,

particularly in the

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder cycles,

i.e. Schwanengesang,

Winterreise a... $32.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Classical Fake Book - 2nd Edition

Fake Book [Fake Book] - Facile

Hal Leonard

(Over 850 Classical Themes and Melodies in the Original Keys) For C instrument. ...(+)

(Over 850 Classical

Themes and Melodies in

the Original Keys) For C

instrument. Format:

fakebook (spiral bound).

With vocal melody

(excerpts) and chord

names. Lassical. Series:

Hal Leonard Fake Books.

646 pages. 9x12 inches.

Published by Hal Leonard.

(8)$49.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| The Ultimate Pop/Rock Fake Book - In C

Instruments en Do [Fake Book]

Hal Leonard

(4th Edition ) For voice and C instrument. Format: fakebook. With vocal melody, ...(+)

(4th Edition ) For voice

and C instrument. Format:

fakebook. With vocal

melody, lyrics and chord

names. Pop rock, rock and

pop. Series: Hal Leonard

Fake Books. 584 pages.

9x12 inches. Published by

Hal Leonard.

(26)$49.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| The Real Little Classical Fake Book - 2nd Edition

Piano seul - Intermédiaire

Hal Leonard

Composed by Various. For Piano/Keyboard. Hal Leonard Fake Books. Classical. Diff...(+)

Composed by Various. For

Piano/Keyboard. Hal

Leonard Fake Books.

Classical. Difficulty:

medium to

medium-difficult.

Fakebook. Melody line,

chord names and lyrics

(on some songs). 413

pages. Published by Hal

Leonard

$27.50 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| ARKA - 3 Rituale (Full Score)

Voix basse, Piano [Conducteur]

Peters

Orchestra solo oboe, solo pipa, timpani 4 Pauken, 1 Spieler, percussion, (Crotal...(+)

Orchestra solo oboe, solo

pipa, timpani 4 Pauken, 1

Spieler, percussion,

(Crotali, Glockenspiel,

gr, Trommel,

vibraphonerafon - 1

Spieler), strings (7, 1)

SKU: PE.EP14445

Composed by Bernd Franke.

Full Scores. Edition

Peters. Score. 52 pages.

Duration 00:20:00.

Edition Peters

#98-EP14445. Published by

Edition Peters

(PE.EP14445). ISBN

9790014135041. 297 x 420

mm inches.

German. ARKA

stammt aus dem

Sanskrit und bedeutet so

viel wie Strahl, Blitz,

Sonne, Licht, aber auch

Lied, Feuer und Hymnus,

und entwickelt in meiner

Vorstellung sehr viele

unterschiedliche

Assoziationsfelder. In

ARKA stecken

auch die Worter arc

(beten) und ka (Wasser),

und es kann auch

ubersetzt werden mit:

,,Das Wasser stromt aus

dem heraus, der mehr

weiss. Mein neues

Werk fur Pipa, Oboe,

Pauke, Schlagzeug und

Orchester entstand im

Auftrag der

Kammerakademie Neuss und

auf Anregung des Oboisten

Christian Wetzel. Es

entstanden drei Rituale

mit zum Teil szenischen

Elementen fur die

Solisten und das

Orchester.

Inspirationsquelle in

der Vorbeschaftigung

waren zwei Quellen und

Bucher. Das Daodejing von

Laozi in der

hervorragenden

Neuubersetzung von Viktor

Kalinke, eine der

wichtigsten Quellen

chinesischen Denkens und

der Philosophie dieser

grossen Kulturtradition

und die chinesische

Tradition der

5-Elementelehre und der

Wandlungsphasen. Als

zweites Buch hat mich

,,Die Glut von Roberto

Calasso inspiriert, ein

Buch uber die indischen

Veden in Verbindung mit

den Ursprungen des

Buddhismus und den damit

verbunden Ritualen.

In den letzten 20

Jahren habe ich mich

intensiv mit

ostasiatischer Musik,

Kunst und Philosophie

beschaftigt und habe das

auch durch langere

Studienreisen und

kompositorische Projekte

vertiefen konnen. U.a.

wurde 2012 mein Chorwerk

PRAN in Kolkata in Indien

uraufgefuhrt

(Goethe-Institut),

ebenfalls 2012 ,,in

between VI fur Sho und

Sheng in Tokyo und 2013

,,Mirror and Circle fur

Pipa, Cello und

chinesisches Orchester in

Taipeh/Taiwan

(Auftragswerk der

taiwanesischen

Regierung). Mit der

chinesischen

Pipa-Virtuosin Ya Dong

arbeite ich seit 2000

zusammen und habe fur sie

mehrfach komponiert

(Urauffuhrungen u.a. in

Hannover/EXPO 2000,

Rottweil 2001, Taipeh

2013, Magdeburg 2016).

Auch mit Christian Wetzel

arbeite ich seit uber 20

Jahren zusammen und habe

ebenfalls haufig fur ihn

komponiert (UA u.a. in

Bonn 1999, Hannover/EXPO

2000, Rottweil 2001,

Darmstadt 2004 und

etliche weitere

Projekte). Jedes

dieser drei Rituale hat

eine Lange von ca. 6-7

Minuten und stellt

unterschiedliche

Qualitaten und

Besonderheiten der beiden

Soloinstrumente heraus,

immer in Verbindung mit

der Interaktion zwischen

Soli und Orchester. Die

Besetzung war fur mich

ausserst reizvoll, da

beide Instrumente in

dieser Kombination noch

nie so erklungen sind.

Die Pipa ist ein ungemein

modernes und

ungewohnliches

Instrument, reich an

Farben und vor allem an

perkussiven Effekten. Das

Tonmaterial wurde zum

grossten Teil aus den

Namen der beiden Solisten

gewonnen und ergibt

interessanter zwei

gespiegelte

Viertonmotive. In der

asiatischen Kultur

spielen der Spiegel und

der Kreis eine wichtige

Rolle, und so werden die

Tone, Rhythmen und Formen

eingewoben in diese drei

Rituale, welche am Ende

des dritten Satzes wieder

kreisformig an den Anfang

des ersten Rituals

anknupfen. Ein von den

Streichern und der Pauke

erzeugtes Gerausch,

verbunden mit dem

Rhythmus der grossen

Trommel, welcher einen

Herzschlag symbolisieren

soll. Die drei Untertitel

der Rituale Himmel, Erde

und (atmospharischer)

Raum spielen im vedischen

und chinesischen Denken

eine grosse Rolle und war

fur mich beim Komponieren

ebenfalls eine sehr

starke

Inspirationsquelle. In

vielen meiner

Kompositionen gibt es

Raumeffekte, Annaherungen

an das Publikum, das

Verschieben von

Perspektiven, die

Dekonstruktion und das

Hinterfragen der ublichen

Konzertsituation, so u.a

in meinem Beuys-Zyklus

oder in den Zyklen ,,CUT

und ,,in between.

In ARKA geht

es mir besonders um die

Interaktion zwischen

westlichem und ostlichem

Denken, um das

gegenseitige Durchdringen

dieser auf den ersten

Blick so

unterschiedlichen Denk-

und Lebensweisen, um eine

Verschmelzung scheinbarer

Gegensatze - um

Annaherung! Bernd

Franke. Leipzig,

11.10.2019 W01476|C|Y

0.0000 Sheet Music

_x000D_ 9780193556799 Y

23.50 X556799 357665

9780193556799 MISC C 1

432 8030 0.00 Oxford Solo

Songs: Christmas 14 songs

with piano PAPER 14

9780193556799 A-B CAROLS

CHRISTMAS MISC

MISCELLANEOUS OXFORD

PIANO SOLO SONGS SONGS:

VOICE WITH AB 00:00:0 Low

voice & piano Low voice

book + downloadable

backing tracks 311x232 72

NEW NONE 29/07/2021 P

355580 9780193556799

- Young: A babe is

born

- Rutter:

Angels' Carol

-

McDowall: Before the

paling of the stars

- Rutter:

Candlelight Carol

- Rutter: I sing

of a maiden

-

Chilcott: Mid-winter

- Todd: My Lord

has Come

-

Bullard: Scots Nativity

- Quartel: Snow

Angel

- Todd:

Softly

-

Chilcott: Sweet was the

song

- Chilcott:

The Shepherd's Carol

- Quartel: This

endris night

-

McGlade: What child is

this?

for

low voice and piano

This beautiful

collection of 14 songs

for low voice offers

Christmas settings by

some of Oxford's

best-loved composers.

Suitable for solo singers

and unison choirs alike,

each song is presented

with piano accompaniment,

and high-quality,

downloadable backing

tracks are included on a

companion website. With a

wonderful selection of

pieces, including

favourites such as Bob

Chilcott's 'The

Shepherd's Carol' and

John Rutter's

'Candlelight Carol', this

is the perfect collection

for use in carol services

and Christmas concerts or

for enjoying at home.

Also available in a

volume for high voice and

piano. - 14

songs for solo

voice

- Well-loved

composers, including John

Rutter and Bob

Chilcott

- Wide

selection of Christmas

texts

- Accessible

accompaniments

-

Includes backing tracks

downloadable from a

Companion

Website

-

Available in volumes for

high and low

voice

MISC|AU|Y

0.0000 Paperback _x000D_

EP73308R Y 0.00 73308R

P73308R 1 ORCHA 8000 0.00

Hover A (LARGE) BEAMISH

EP73308R GP:ORCHESTRAL

HOVER ONLY RENTAL SALLY

WORKS NONE ORCHA P 303000

EP73308R 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP14437A Y

22.95 14437A P14437A

FRANKE, BERND C

9790014137199 52A1 8000

0.00 AGNI A 9790014137199

AGNI BASS BERND CLARINET

EP14437A FRANKE

PHOTOPRINTS W01476

English / German 00:12:0

Instrumental Score 232 x

303 mm Bass clarinet 20

DETNT NEW PR43 23/04/2021

P 303006 AGNI is the

Hindu god of fire; the

elemental and

transformative force

inherent in

everything: Every

flame, every fire, every

light, every warmth is

AGNI. AGNI is

omnipresent, establishing

everything and ending

everything. AGNI is

often depicted with seven

tongues which represent

different aspects of his

being. These

include: creating,

sustaining, cleansing,

purifying, priestly,

martial, devastating,

destructive, and

consuming. Derived

from Franke's concerto of

the same name, this solo

work for bass clarinet

compositionally traces

the transformative

processes initiated by

the divine fire. The solo

takes seven pieces from

the concerto, presenting

vivid character pieces

exploring the creative

possibilities and wide

tonal range offered by

the bass

clarinet. This

version of AGNI

for bass clarinet solo

was premiered on 4

December 2020 in Leipzig

by Volker Hemken, the

principal bass

clarinetist of the

Gewandhausorchester

Leipzig. EP14437a

convinces with its

excellent and clear

notation, making the

piece a new standard for

bass clarinet.

W01476|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP68686 Y

165.00 68686 P68686 LEWIS

C 9790300761299 97 8000

0.00 Ikons A

9790300761299

CONTEMPORARY ENSEMBLE

EP68686 GEORGE IKONS

LEWIS PHOTOPRINTS SMALL

W06652 English 00:14:0

Conductor Score & Parts

303 x 232 mm Fl (A-fl in

F).Cl.Bsn

(Cbsn).Tbn.Perc.Vln.Vlc.C

b 132 NEW PR43 USTNT

21/04/2021 P 303006

Ikons,

commissioned by the

Vancouver Cultural

Olympiad 2010, exists in

two forms. This 14-minute

acoustic version,

premiered by the Turning

Point Ensemble, calls for

an octet of live

musicians to execute

complex rhythms and

quarter-tone

harmonies. The

interactive, electronic

version, created with

visual artist Eric

Metcalfe and designed to

be presented separately,

incorporates samples from

this acoustic version

into a sculptural

environment of seven

pyramidal structures that

respond sonically to the

viewer. W06652|C|Y

0.0000 Sheet Music

_x000D_ EP73531 Y 31.95

73531 P73531 PANUFNIK,

ROXANNA C 9790577020976

61 8000 0.00 Sonnets

without Words A

9790577020976 EP73531

HORN PANUFNIK PHOTOPRINTS

PIANO ROXANNA SHAKESPEARE

SONNETS W03578 WILLIAM

WITHOUT WORDS English

Score & Instrumental

Parts 232 x 303 mm Horn

and piano 28 NEW PR43

UKTNT 21/04/2021 P 303006

Roxanna Panufnik's

Sonnets without

Words is a

contemporary piece for

Horn in F and piano.

Written for horn player

Ben Goldscheider,

Panufnik has reimagined

the lyrical vocal lines

from three of her

previous settings of

Shakespeare's sonnets

(Mine eye, Music to

hear and Sweet

Love Remember'd for

voice and piano) into a

purely instrumental

work. Score and

horn

part. - Contempo

rary work for Horn in F

and

piano

- Settings of

Sheakespeare's Sonnets 8,

24 & 29 in instrumental

form

W03578|C|Y

W06737|LY|N 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP73571 Y

15.95 73571 P73571

MCNEFF, STEPHEN C

9790577021317 20 8000

0.00 Trig for Solo Cello

A 9790577021317 (SOLO)

CELLO EP73571 MCNEFF

PHOTOPRINTS SOLO STEPHEN

TRIG W03150 English

00:07:0 Instrumental

Score 232 x 303 mm Solo

Violoncello 8 NEW PR43

UKTNT 21/04/2021 P 303006

Stephen McNeff's

Trig is a short

7-minute contemporary

work for solo cello,

written to celebrate the

bicentennial of the Royal

Academy of Music in 2022

and in memorium cellist

Mike Edwards

1948-2010. Trig

was premiered by

Henry Hargreaves on 19

March 2021, livestreamed

from the Royal Academy of

Music. - Contemp

orary piece for solo

cello

- Written for

the Royal Academy of

Music's

bicentennial

W03150|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP14528 Y

34.95 14528 P14528

SAUNDERS, REBECCA C

9790014136796 3 8000 0.00

to an utterance - study A

9790014136796 (SOLO) AN

EP14528 PHOTOPRINTS PIANO

REBECCA SAUNDERS STUDY TO

UTTERANCE W04191 English

Instrumental Score 420 x

297 mm Piano Solo 16

DETNT NEW PR43 21/04/2021

P 303006 to an

utterance - study

was commissioned by

Klangforum Wien for the

premiere commercial audio

recording on a portrait

CD in 2020 and first

performed by Joonas

Ahonen at the Berlin

Philharmonie on 4th

September 2020 at the

Musikfest Berlin.

W04191|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP71880 Y

75.00 71880 P71880

PANUFNIK, ROXANNA C

9790577008332 82 8000

0.00 Spirit Moves for

Brass Quintet A

9790577008332 BRASS

ENSEMBLE EP71880 MOVES

PANUFNIK PHOTOPRINTS

QUINTET ROXANNA SPIRIT

W03578 English 00:15:0

Score & Instrumental

Parts 232 x 303 mm

Trumpet 1 in B flat

(doubling Piccolo

Trumpet), Trumpet 2 in B

flat (doubling Flugel

Horn), Horn in F,

Trombone, Tuba 84 NEW

PR43 UKTNT 21/04/2021 P

303006 Roxanna

Panufnik's Spirit

Moves, for brass

quintet, was commissioned

by the Fine Arts Brass

Ensemble. This 15-minute

piece is scored for two

trumpets in Bb (one

doubling piccolo trumpet

and the other doubling

flugel horn), horn in F,

trombone and tuba. This

brass quintet is so

called because the outer

movements are highly

spirited and the

central one is

spiritual. This product consists of

score and parts.

W03578|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP73585 Y

4.00 73585 P73585 369282

WILLIAMS, RODERICK C

9790577021591 1 151 8000

0.00 Eriskay Love Lilt A

9790577021591 (SECULAR)

CHORAL EP73585 ERISKAY

HALSTAN-USA LILT LOVE

RODERICK TRADITIONAL

W05152 WILLIAMS WORKS

English 00:03:0 190 x 272

mm SATB (divisi) and

piano 16 NEW PR30 UKTNT

20/05/2021 P 377788 A

gently flowing 3-minute

arrangement by Roderick

Williams for SATB (with

divisi) with piano

accompaniment that

captures the beauty of

this famous traditional

Hebridean love song. The

song text uses both old

dialect and English, each

verse ending with the

words, 'Sad am I without

thee'. - Commiss

ioned by The Sixteen

choir and recorded on

their 2021 album

'Goodnight

Beloved'

- Roderick

Williams is a

composer/arranger and

also a world-renowned

baritone

- The

arrangement is described

by Williams as 'having a

little nod to Ravel and

Grieg'

W05152|C|Y W04819|LY|N

0.0000 Sheet Music

_x000D_ 9780193556782 Y

23.50 X556782 357665

9780193556782 MISC C 1

432 8030 0.00 Oxford Solo

Songs: Christmas 14 songs

with piano PAPER 14

9780193556782 A-B CAROLS

CHRISTMAS MISC

MISCELLANEOUS OXFORD

PIANO SOLO SONGS SONGS:

VOICE WITH AB 00:00:0

High voice & piano High

voice book + downloadable

backing tracks 311x232 72

NEW NONE 29/07/2021 P

355580 9780193556782

- Young: A babe is

born

- Rutter:

Angels' Carol

-

McDowall: Before the

paling of the stars

- Rutter:

Candlelight Carol

- Rutter: I sing

of a maiden

-

Chilcott: Mid-winter

- Todd: My Lord

has Come

-

Bullard: Scots Nativity

- Quartel: Snow

Angel

- Todd:

Softly

-

Chilcott: Sweet was the

song

- Chilcott:

The Shepherd's Carol

- Quartel: This

endris night

-

McGlade: What child is

this?

for

high voice and piano

This beautiful

collection of 14 songs

for high voice offers

Christmas settings by

some of Oxford's

best-loved composers.

Suitable for solo singers

and unison choirs alike,

each song is presented

with piano accompaniment,

and high-quality,

downloadable backing

tracks are included on a

companion website. With a

wonderful selection of

pieces, including

favourites such as Bob

Chilcott's 'The

Shepherd's Carol' and

John Rutter's

'Candlelight Carol', this

is the perfect collection

for use in carol services

and Christmas concerts or

for enjoying at home.

Also available in a

volume for low voice and

piano. - 14

songs for solo high

voice

- Well-loved

composers, including John

Rutter and Bob

Chilcott

- Wide

selection of sacred and

secular Christmas

texts

- Accessible

accompaniments

-

Includes backing tracks

downloadable from a

Companion

Website

-

Available in volumes for

high and low solo

voice

MISC|AU|Y

0.0000 Paperback _x000D_

9780193559066 Y 4.25

X559066 357665

9780193559066 YOUNG C 1

444 8030 0.00 O splendour

of God's glory bright

PAPER 9780193559066

BRIGHT CHORAL GLORY GOD'S

MIXED OF OXFORD SACRED

SPLENDOUR TOBY VOICES

W06576 YOUNG C 00:03:30

SATB & organ Vocal score

254x178 SATB 20 NONE P

355580 9780193559066

for SATB and organ

This energetic

setting of words by St

Ambrose of Milan is a

real showstopper. With

pop-influences and a

sparkling organ part,

Young effortlessly fuses

modern and traditional

sound worlds, while

changes in key and metre

build up to an

invigorating finish.

Perfect for accomplished

choirs looking for

something different.

W06576|C|Y 0.0000

Paperback _x000D_

9780193554399 Y 2.60

X554399 357665

9780193554399 LASSUS,

ORLANDO DE C 1 445 8030

0.00 Oculus non vidit

PAPER 9780193554399

CHORAL DE KEANE LASSUS

MARK NON OCULUS ORLANDO

OXFORD SACRED UPPER VIDIT

VOICES W02750 B 00:01:30

SA unaccompanied Vocal

score 254x178 Upper

Voices - 3 parts or more

4 NONE 10/06/2021 P

355580 9780193554399

for SA unaccompanied

This simple, charming

two-part motet features

long melismatic phrases

that reflect the text (1

Corinthians 2: 9), such

as the rising melodic

line over three bars on

the word 'ascended'

(ascendit).

W02750|C|Y

W06960|E|N 0.0000

Paperback _x000D_

9780193954298 Y 3.35

X954298 357665

9780193954298 TALLIS,

THOMAS C 1 448 8030 0.00

Honor, virtus et potestas

PAPER 9780193954298

CANTICLES DUNKLEY ET

HONOR OXFORD POTESTAS

SALLY SERVICES TALLIS

THOMAS VIRTUS W04705 C

00:06:0 SAATB

unaccompanied Vocal score

MSER00020 SATB 12 NONE

28/05/2021 P 355580

9780193954298 for

SAATB unaccompanied.

This glorious musical

depiction of the honour,

strength, power and

authority of the Holy

Trinity by Thomas Tallis

is the third issue in the

CMS's series of great

English Responds from the

16th century, edited by

Sally Dunkley. Scored for

SAATB, it can be

performed either as a

motet or as a full

Responsory with plainsong

alternating with

polyphony. W04705|C|Y

W01184|E|N 0.0000

Paperback _x000D_ EP73527

Y 6.95 73527 P73527

BEAMISH, SALLY C

9790577020891 50 8000

0.00 The Parting Glass A

9790577020891 (SOLO)

BEAMISH CLARINET EP73527

GLASS PARTING PHOTOPRINTS

SALLY W00306 English

Score 232 x 303 mm

Clarinet 4 NEW PR43 UKTNT

12/12/2020 P 303006

Based on a traditional

Scottish/Irish 'farewell'

song, this short piece is

one of six works written

to express my love of

Scotland. After living

there for nearly half my

life, and raising a

family, I moved back to

England in 2018, and

remarried in 2019.

Of course, there were

many different emotions

attached to the move

south: especially the joy

and excitement of new

beginnings, and

reconnection with friends

from my youth.

But this piece

expresses the wrench I

experienced after a last

family meal in Glasgow,

and the realisation of

all I was about to leave

behind. I have

taken the melody of the

original song, and

expanded it, exploring

the detail of its

patterns, so that it

becomes a timeless

meditation. The

six pieces in the

'farewell' series are for

6 violas, string quintet,

string quartet, trio,

violin and clarinet duo,

and solo clarinet.

The Parting Glass

was composed in 2020

during the coronavirus

lockdown, which

intensified the feeling

of separation from my

Scottish family, as well

as from other musicians.

It was

commissioned by Vittorio

Ceccanti for the

ContempoArtEnsemble.

W00306|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP73516 Y

6.95 73516 P73516

BEAMISH, SALLY C

9790577020747 20 8000

0.00 Maple A

9790577020747 (SOLO)

BEAMISH CELLO EP73516

MAPLE PHOTOPRINTS SALLY

W00306 English 00:06:0

Score 232 x 303 mm

Contemporary cello solo 8

NEW PR43 UKTNT 12/12/2020

P 303006 Seed; Spinning

Seed; Roots, shoots;

Leaves ; Flowers; Tree ;

Autumn ; Cello

Maple arose

from a commission to

write a work for solo

cello, to be performed

alongside readings from

artist John Newling's

collection of letters

entitled 'Dear Nature'; a

poetic manifestation of

our relationship with the

natural world. The

piece is in eight short

sections, to be

interspersed with

readings of groups of the

poems. It may also be

performed as a single

movement. It begins with

a seed - the seed of a

maple tree, as it hangs

on the mature tree, ready

to drop. The seeds are

like propellers,

sometimes travelling more

than a mile before

landing on the ground.

Maple follows

the growth of the tree to

maturity - which in

reality would take at

least a hundred years.

'Roots, shoots' grows

downwards and upwards

from a pedal note, and

the dance-like 'Flowers'

is followed by the

stately 'Tree', and then

the warm, cascading

'Autumn'. Maple is very

often the wood of choice

for the back of a

stringed instrument, and

the last section uses

open strings to explore

the full resonance of the

cello. The piece

starts with a 'seed' of

only five notes, which

grows into different

configurations. It is

intended to be played in

an improvisatory

style.

Maple was

co-commissioned by

Brighton Festival, Ars et

Terra Festival with SACEM

and Ditchling Arts and

Crafts Museum, to be

performed by Margarita

Balanas as part of the

Brighton Festival's 'Dear

Nature' project.

W00306|C|Y 0.0000 Sheet

Music _x000D_ EP73508 Y

39.95 73508 P73508

DILLON, JAMES C

9790577020648 3 8000 0.00

echo the angelus A

9790577020648 (SOLO)

ANGELUS DILLON ECHO

EP73508 JAMES PHOTOPRINTS

PIANO W01097 English

00:25:0 Score 232 x 303

mm Piano Solo 44 NEW PR43

UKTNT 12/01/2021 P 303006

First performed by

Noriko Kawai for

Huddersfield Contemporary

Music Festival, in a

broadcast from the Radio

Theatre, BBC Broadcasting

House, November

2020. Full of

beautifully crafted,

delicate

tintinnabulations -

Richard Morrison, The

Times This

product is Printed on

Demand and may take

several weeks to fulfill.

Please order from your

favorite retailer. $90.00 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Concerto - Piano And Orchestra - Solo Part

Schott

Piano and orchestra - difficult SKU: HL.49046544 For piano and orchest...(+)

Piano and orchestra -

difficult SKU:

HL.49046544 For

piano and orchestra.

Composed by Gyorgy

Ligeti. This edition:

Saddle stitching. Sheet

music. Edition Schott.

Softcover. Composed

1985-1988. Duration 24'.

Schott Music #ED23178.

Published by Schott Music

(HL.49046544). ISBN

9781705122655. UPC:

842819108726.

9.0x12.0x0.224

inches. I composed

the Piano Concerto in two

stages: the first three

movements during the

years 1985-86, the next

two in 1987, the final

autograph of the last

movement was ready by

January, 1988. The

concerto is dedicated to

the American conductor

Mario di Bonaventura. The

markings of the movements

are the following: 1.

Vivace molto ritmico e

preciso 2. Lento e

deserto 3. Vivace

cantabile 4. Allegro

risoluto 5. Presto

luminoso.The first

performance of the

three-movement Concerto

was on October 23rd, 1986

in Graz. Mario di

Bonaventura conducted

while his brother,

Anthony di Bonaventura,

was the soloist. Two days

later the performance was

repeated in the Vienna

Konzerthaus. After

hearing the work twice, I

came to the conclusion

that the third movement

is not an adequate

finale; my feeling of

form demanded

continuation, a

supplement. That led to

the composing of the next

two movements. The

premiere of the whole

cycle took place on

February 29th, 1988, in

the Vienna Konzerthaus

with the same conductor

and the same pianist. The

orchestra consisted of

the following: flute,

oboe, clarinet, bassoon,

horn, trumpet, tenor

trombone, percussion and

strings. The flautist

also plays the piccoIo,

the clarinetist, the alto

ocarina. The percussion

is made up of diverse

instruments, which one

musician-virtuoso can

play. It is more

practical, however, if

two or three musicians

share the instruments.

Besides traditional

instruments the

percussion part calls

also for two simple wind

instruments: the swanee

whistle and the

harmonica. The string

instrument parts (two

violins, viola, cello and

doubles bass) can be

performed soloistic since

they do not contain

divisi. For balance,

however, the ensemble

playing is recommended,

for example 6-8 first

violins, 6-8 second, 4-6

violas, 4-6 cellos, 3-4

double basses. In the

Piano Concerto I realized

new concepts of harmony

and rhythm. The first

movement is entirely

written in bimetry:

simultaneously 12/8 and

4/4 (8/8). This relates

to the known triplet on a

doule relation and in

itself is nothing new.

Because, however, I

articulate 12 triola and

8 duola pulses, an

entangled, up till now

unheard kind of polymetry

is created. The rhythm is

additionally complicated

because of asymmetric

groupings inside two

speed layers, which means

accents are

asymmetrically

distributed. These

groups, as in the talea

technique, have a fixed,

continuously repeating

rhythmic structures of

varying lengths in speed

layers of 12/8 and 4/4.

This means that the

repeating pattern in the

12/8 level and the

pattern in the 4/4 level

do not coincide and

continuously give a

kaleidoscope of renewing

combinations. In our

perception we quickly

resign from following

particular rhythmical

successions and that what

is going on in time

appears for us as

something static,

resting. This music, if

it is played properly, in

the right tempo and with

the right accents inside

particular layers, after

a certain time 'rises, as

it were, as a plane after

taking off: the rhythmic

action, too complex to be

able to follow in detail,

begins flying. This

diffusion of individual

structures into a

different global

structure is one of my

basic compositional

concepts: from the end of

the fifties, from the

orchestral works

Apparitions and

Atmospheres I

continuously have been

looking for new ways of

resolving this basic

question. The harmony of

the first movement is

based on mixtures, hence

on the parallel leading

of voices. This technique

is used here in a rather

simple form; later in the

fourth movement it will

be considerably

developed. The second

movement (the only slow

one amongst five

movements) also has a

talea type of structure,

it is however much

simpler rhythmically,

because it contains only

one speed layer. The

melody is consisted in

the development of a

rigorous interval mode in

which two minor seconds

and one major second

alternate therefore nine

notes inside an octave.

This mode is transposed

into different degrees

and it also determines

the harmony of the

movement; however, in

closing episode in the

piano part there is a

combination of diatonics

(white keys) and

pentatonics (black keys)

led in brilliant,

sparkling quasimixtures,

while the orchestra

continues to play in the

nine tone mode. In this

movement I used isolated

sounds and extreme

registers (piccolo in a

very low register,

bassoon in a very high

register, canons played

by the swanee whistle,

the alto ocarina and

brass with a harmon-mute'

damper, cutting sound

combinations of the

piccolo, clarinet and

oboe in an extremely high

register, also

alternating of a

whistle-siren and

xylophone). The third

movement also has one

speed layer and because

of this it appears as

simpler than the first,

but actually the rhythm

is very complicated in a

different way here. Above

the uninterrupted, fast

and regular basic pulse,

thanks to the asymmetric

distribution of accents,

different types of

hemiolas and inherent

melodical patterns appear

(the term was coined by

Gerhard Kubik in relation

to central African

music). If this movement

is played with the

adequate speed and with

very clear accentuation,

illusory

rhythmic-melodical

figures appear. These

figures are not played

directly; they do not

appear in the score, but

exist only in our

perception as a result of

co-operation of different

voices. Already earlier I

had experimented with

illusory rhythmics,

namely in Poeme

symphonique for 100

metronomes (1962), in

Continuum for harpsichord

(1968), in Monument for

two pianos (1976), and

especially in the first

and sixth piano etude

Desordre and Automne a

Varsovie (1985). The

third movement of the

Piano Concerto is up to

now the clearest example

of illusory rhythmics and

illusory melody. In

intervallic and chordal

structure this movement

is based on alternation,

and also inter-relation

of various modal and

quasi-equidistant harmony

spaces. The tempered

twelve-part division of

the octave allows for

diatonical and other

modal interval

successions, which are

not equidistant, but are

based on the alternation

of major and minor

seconds in different

groups. The tempered

system also allows for

the use of the

anhemitonic pentatonic

scale (the black keys of

the piano). From

equidistant scales,

therefore interval

formations which are

based on the division of

an octave in equal

distances, the

twelve-tone tempered

system allows only

chromatics (only minor

seconds) and the six-tone

scale (the whole-tone:

only major seconds).

Moreover, the division of

the octave into four

parts only minor thirds)

and three parts (three

major thirds) is

possible. In several

music cultures different

equidistant divisions of

an octave are accepted,

for example, in the

Javanese slendro into

five parts, in Melanesia

into seven parts, popular

also in southeastern

Asia, and apart from

this, in southern Africa.

This does not mean an

exact equidistance: there

is a certain tolerance

for the inaccurateness of

the interval tuning.

These exotic for us,

Europeans, harmony and

melody have attracted me

for several years.

However I did not want to

re-tune the piano

(microtone deviations

appear in the concerto

only in a few places in

the horn and trombone

parts led in natural

tones). After the period

of experimenting, I got

to pseudo- or

quasiequidistant

intervals, which is

neither whole-tone nor

chromatic: in the

twelve-tone system, two

whole-tone scales are

possible, shifted a minor

second apart from each

other. Therefore, I

connect these two scales

(or sound resources), and

for example, places occur

where the melodies and

figurations in the piano

part are created from

both whole tone scales;

in one band one six-tone

sound resource is

utilized, and in the

other hand, the

complementary. In this

way whole-tonality and

chromaticism mutually

reduce themselves: a type

of deformed

equidistancism is formed,

strangely brilliant and

at the same time

slanting; illusory