|

| Transcriptions of Lieder

Piano seul

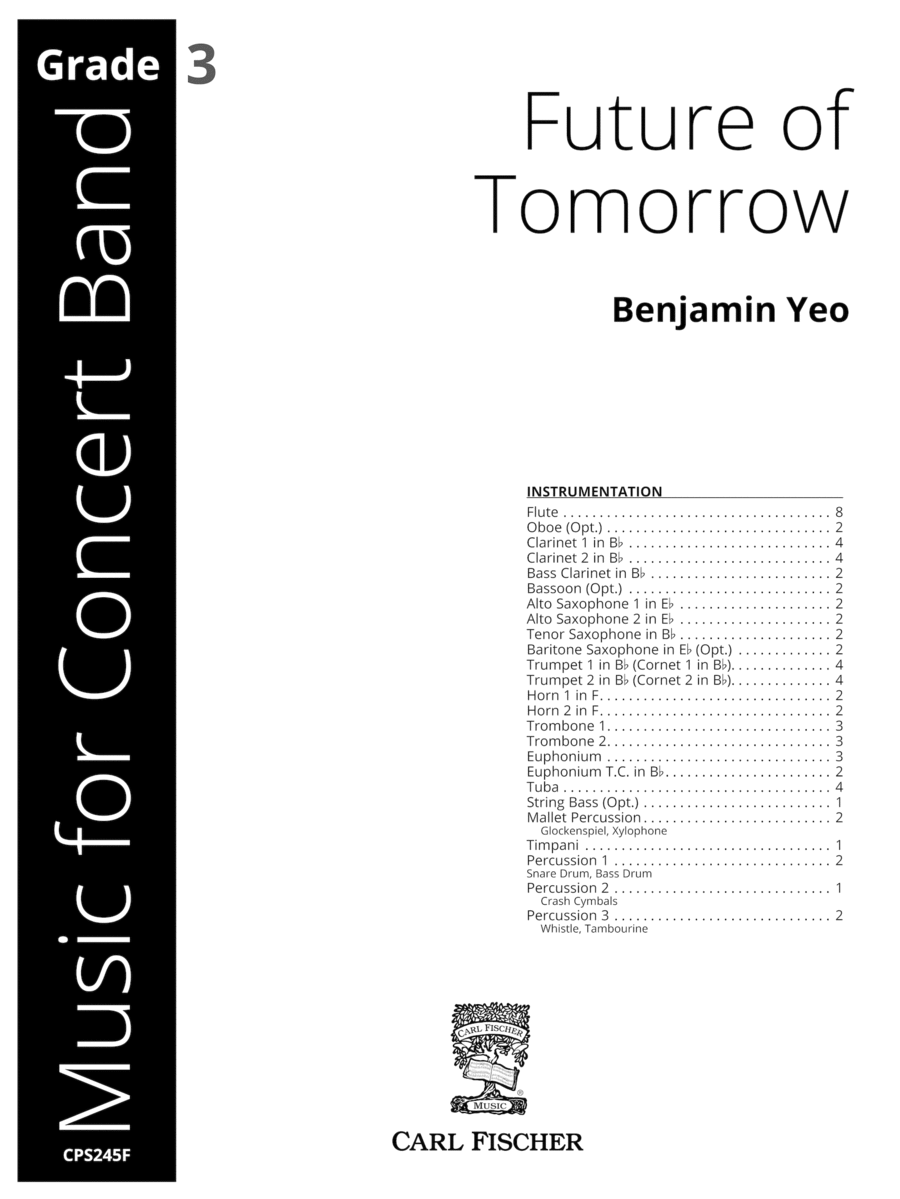

Carl Fischer

Chamber Music Piano SKU: CF.PL1056 Composed by Clara Wieck-Schumann, Fran...(+)

Chamber Music Piano

SKU: CF.PL1056

Composed by Clara

Wieck-Schumann, Franz

Schubert, and Robert

Schumann. Edited by

Nicholas Hopkins.

Collection. With Standard

notation. 128 pages. Carl

Fischer Music #PL1056.

Published by Carl Fischer

Music (CF.PL1056).

ISBN 9781491153390.

UPC: 680160910892.

Transcribed by Franz

Liszt. Introduction

It is true that Schubert

himself is somewhat to

blame for the very

unsatisfactory manner in

which his admirable piano

pieces are treated. He

was too immoderately

productive, wrote

incessantly, mixing

insignificant with

important things, grand

things with mediocre

work, paid no heed to

criticism, and always

soared on his wings. Like

a bird in the air, he

lived in music and sang

in angelic fashion.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Dr. S. Lebert (1868) Of

those compositions that

greatly interest me,

there are only Chopin's

and yours. --Franz Liszt,

letter to Robert Schumann

(1838) She [Clara

Schumann] was astounded

at hearing me. Her

compositions are really

very remarkable,

especially for a woman.

There is a hundred times

more creativity and real

feeling in them than in

all the past and present

fantasias by Thalberg.

--Franz Liszt, letter to

Marie d'Agoult (1838)

Chretien Urhan

(1790-1845) was a

Belgian-born violinist,

organist and composer who

flourished in the musical

life of Paris in the

early nineteenth century.

According to various

accounts, he was deeply

religious, harshly

ascetic and wildly

eccentric, though revered

by many important and

influential members of

the Parisian musical

community. Regrettably,

history has forgotten

Urhan's many musical

achievements, the most

important of which was

arguably his pioneering

work in promoting the

music of Franz Schubert.

He devoted much of his

energies to championing

Schubert's music, which

at the time was unknown

outside of Vienna.

Undoubtedly, Urhan was

responsible for

stimulating this

enthusiasm in Franz

Liszt; Liszt regularly

heard Urhan's organ

playing in the

St.-Vincent-de-Paul

church in Paris, and the

two became personal

acquaintances. At

eighteen years of age,

Liszt was on the verge of

establishing himself as

the foremost pianist in

Europe, and this

awakening to Schubert's

music would prove to be a

profound experience.

Liszt's first travels

outside of his native

provincial Hungary were

to Vienna in 1821-1823,

where his father enrolled

him in studies with Carl

Czerny (piano) and

Antonio Salieri (music

theory). Both men had

important involvements

with Schubert; Czerny

(like Urhan) as performer

and advocate of

Schubert's music and

Salieri as his theory and

composition teacher from

1813-1817. Curiously,

Liszt and Schubert never

met personally, despite

their geographical

proximity in Vienna

during these years.

Inevitably, legends later

arose that the two had

been personal

acquaintances, although

Liszt would dismiss these

as fallacious: I never

knew Schubert personally,

he was once quoted as

saying. Liszt's initial

exposure to Schubert's

music was the Lieder,

what Urhan prized most of

all. He accompanied the

tenor Benedict

Randhartinger in numerous

performances of

Schubert's Lieder and

then, perhaps realizing

that he could benefit the

composer more on his own

terms, transcribed a

number of the Lieder for

piano solo. Many of these

transcriptions he would

perform himself on

concert tour during the

so-called Glanzzeit, or

time of splendor from

1839-1847. This publicity

did much to promote

reception of Schubert's

music throughout Europe.

Once Liszt retired from

the concert stage and

settled in Weimar as a

conductor in the 1840s,

he continued to perform

Schubert's orchestral

music, his Symphony No. 9

being a particular

favorite, and is credited

with giving the world

premiere performance of

Schubert's opera Alfonso

und Estrella in 1854. At

this time, he

contemplated writing a

biography of the

composer, which

regrettably remained

uncompleted. Liszt's

devotion to Schubert

would never waver.

Liszt's relationship with

Robert and Clara Schumann

was far different and far

more complicated; by

contrast, they were all

personal acquaintances.

What began as a

relationship of mutual

respect and admiration

soon deteriorated into

one of jealousy and

hostility, particularly

on the Schumann's part.

Liszt's initial contact

with Robert's music

happened long before they

had met personally, when

Liszt published an

analysis of Schumann's

piano music for the

Gazette musicale in 1837,

a gesture that earned

Robert's deep

appreciation. In the

following year Clara met

Liszt during a concert

tour in Vienna and

presented him with more

of Schumann's piano

music. Clara and her

father Friedrich Wieck,

who accompanied Clara on

her concert tours, were

quite taken by Liszt: We

have heard Liszt. He can

be compared to no other

player...he arouses

fright and astonishment.

His appearance at the

piano is indescribable.

He is an original...he is

absorbed by the piano.

Liszt, too, was impressed

with Clara--at first the

energy, intelligence and

accuracy of her piano

playing and later her

compositions--to the

extent that he dedicated

to her the 1838 version

of his Etudes d'execution

transcendante d'apres

Paganini. Liszt had a

closer personal

relationship with Clara

than with Robert until

the two men finally met

in 1840. Schumann was

astounded by Liszt's

piano playing. He wrote

to Clara that Liszt had

played like a god and had

inspired indescribable

furor of applause. His

review of Liszt even

included a heroic

personification with

Napoleon. In Leipzig,

Schumann was deeply

impressed with Liszt's

interpretations of his

Noveletten, Op. 21 and

Fantasy in C Major, Op.

17 (dedicated to Liszt),

enthusiastically

observing that, I feel as

if I had known you twenty

years. Yet a variety of

events followed that

diminished Liszt's glory

in the eyes of the

Schumanns. They became

critical of the cult-like

atmosphere that arose

around his recitals, or

Lisztomania as it came to

be called; conceivably,

this could be attributed

to professional jealousy.

Clara, in particular,

came to loathe Liszt,

noting in a letter to

Joseph Joachim, I despise

Liszt from the depths of

my soul. She recorded a

stunning diary entry a

day after Liszt's death,

in which she noted, He

was an eminent keyboard

virtuoso, but a dangerous

example for the

young...As a composer he

was terrible. By

contrast, Liszt did not

share in these negative

sentiments; no evidence

suggests that he had any

ill-regard for the

Schumanns. In Weimar, he

did much to promote

Schumann's music,

conducting performances

of his Scenes from Faust

and Manfred, during a

time in which few

orchestras expressed

interest, and premiered

his opera Genoveva. He

later arranged a benefit

concert for Clara

following Robert's death,

featuring Clara as

soloist in Robert's Piano

Concerto, an event that

must have been

exhilarating to witness.

Regardless, her opinion

of him would never

change, despite his

repeated gestures of

courtesy and respect.

Liszt's relationship with

Schubert was a spiritual

one, with music being the

one and only link between

the two men. That with

the Schumanns was

personal, with music

influenced by a hero

worship that would

aggravate the

relationship over time.

Nonetheless, Liszt would

remain devoted to and

enthusiastic for the

music and achievements of

these composers. He would

be a vital force in

disseminating their music

to a wider audience, as

he would be with many

other composers

throughout his career.

His primary means for

accomplishing this was

the piano transcription.

Liszt and the

Transcription

Transcription versus

Paraphrase Transcription

and paraphrase were

popular terms in

nineteenth-century music,

although certainly not

unique to this period.

Musicians understood that

there were clear

distinctions between

these two terms, but as

is often the case these

distinctions could be

blurred. Transcription,

literally writing over,

entails reworking or

adapting a piece of music

for a performance medium

different from that of

its original; arrangement

is a possible synonym.

Adapting is a key part of

this process, for the

success of a

transcription relies on

the transcriber's ability

to adapt the piece to the

different medium. As a

result, the pre-existing

material is generally

kept intact, recognizable

and intelligible; it is

strict, literal,

objective. Contextual

meaning is maintained in

the process, as are

elements of style and

form. Paraphrase, by

contrast, implies

restating something in a

different manner, as in a

rewording of a document

for reasons of clarity.

In nineteenth-century

music, paraphrasing

indicated elaborating a

piece for purposes of

expressive virtuosity,

often as a vehicle for

showmanship. Variation is

an important element, for

the source material may

be varied as much as the

paraphraser's imagination

will allow; its purpose

is metamorphosis.

Transcription is adapting

and arranging;

paraphrasing is

transforming and

reworking. Transcription

preserves the style of

the original; paraphrase

absorbs the original into

a different style.

Transcription highlights

the original composer;

paraphrase highlights the

paraphraser.

Approximately half of

Liszt's compositional

output falls under the

category of transcription

and paraphrase; it is

noteworthy that he never

used the term

arrangement. Much of his

early compositional

activities were

transcriptions and

paraphrases of works of

other composers, such as

the symphonies of

Beethoven and Berlioz,

vocal music by Schubert,

and operas by Donizetti

and Bellini. It is

conceivable that he

focused so intently on

work of this nature early

in his career as a means

to perfect his

compositional technique,

although transcription

and paraphrase continued

well after the technique

had been mastered; this

might explain why he

drastically revised and

rewrote many of his

original compositions

from the 1830s (such as

the Transcendental Etudes

and Paganini Etudes) in

the 1850s. Charles Rosen,

a sympathetic interpreter

of Liszt's piano works,

observes, The new

revisions of the

Transcendental Etudes are

not revisions but concert

paraphrases of the old,

and their art lies in the

technique of

transformation. The

Paganini etudes are piano

transcriptions of violin

etudes, and the

Transcendental Etudes are

piano transcriptions of

piano etudes. The

principles are the same.

He concludes by noting,

Paraphrase has shaded off

into

composition...Composition

and paraphrase were not

identical for him, but

they were so closely

interwoven that

separation is impossible.

The significance of

transcription and

paraphrase for Liszt the

composer cannot be

overstated, and the

mutual influence of each

needs to be better

understood. Undoubtedly,

Liszt the composer as we

know him today would be

far different had he not

devoted so much of his

career to transcribing

and paraphrasing the

music of others. He was

perhaps one of the first

composers to contend that

transcription and

paraphrase could be

genuine art forms on

equal par with original

pieces; he even claimed

to be the first to use

these two terms to

describe these classes of

arrangements. Despite the

success that Liszt

achieved with this type

of work, others viewed it

with circumspection and

criticism. Robert

Schumann, although deeply

impressed with Liszt's

keyboard virtuosity, was

harsh in his criticisms

of the transcriptions.

Schumann interpreted them

as indicators that

Liszt's virtuosity had

hindered his

compositional development

and suggested that Liszt

transcribed the music of

others to compensate for

his own compositional

deficiencies.

Nonetheless, Liszt's

piano transcriptions,

what he sometimes called

partitions de piano (or

piano scores), were

instrumental in promoting

composers whose music was

unknown at the time or

inaccessible in areas

outside of major European

capitals, areas that

Liszt willingly toured

during his Glanzzeit. To

this end, the

transcriptions had to be

literal arrangements for

the piano; a Beethoven

symphony could not be

introduced to an

unknowing audience if its

music had been subjected

to imaginative

elaborations and

variations. The same

would be true of the 1833

transcription of

Berlioz's Symphonie

fantastique (composed

only three years

earlier), the

astonishingly novel

content of which would

necessitate a literal and

intelligible rendering.

Opera, usually more

popular and accessible

for the general public,

was a different matter,

and in this realm Liszt

could paraphrase the

original and manipulate

it as his imagination

would allow without

jeopardizing its

reception; hence, the

paraphrases on the operas

of Bellini, Donizetti,

Mozart, Meyerbeer and

Verdi. Reminiscence was

another term coined by

Liszt for the opera

paraphrases, as if the

composer were reminiscing

at the keyboard following

a memorable evening at

the opera. Illustration

(reserved on two

occasions for Meyerbeer)

and fantasy were

additional terms. The

operas of Wagner were

exceptions. His music was

less suited to paraphrase

due to its general lack

of familiarity at the

time. Transcription of

Wagner's music was thus

obligatory, as it was of

Beethoven's and Berlioz's

music; perhaps the

composer himself insisted

on this approach. Liszt's

Lieder Transcriptions

Liszt's initial

encounters with

Schubert's music, as

mentioned previously,

were with the Lieder. His

first transcription of a

Schubert Lied was Die

Rose in 1833, followed by

Lob der Tranen in 1837.

Thirty-nine additional

transcriptions appeared

at a rapid pace over the

following three years,

and in 1846, the Schubert

Lieder transcriptions

would conclude, by which

point he had completed

fifty-eight, the most of

any composer. Critical

response to these

transcriptions was highly

favorable--aside from the

view held by

Schumann--particularly

when Liszt himself played

these pieces in concert.

Some were published

immediately by Anton

Diabelli, famous for the

theme that inspired

Beethoven's variations.

Others were published by

the Viennese publisher

Tobias Haslinger (one of

Beethoven's and

Schubert's publishers in

the 1820s), who sold his

reserves so quickly that

he would repeatedly plead

for more. However,

Liszt's enthusiasm for

work of this nature soon

became exhausted, as he

noted in a letter of 1839

to the publisher

Breitkopf und Hartel:

That good Haslinger

overwhelms me with

Schubert. I have just

sent him twenty-four new

songs (Schwanengesang and

Winterreise), and for the

moment I am rather tired

of this work. Haslinger

was justified in his

demands, for the Schubert

transcriptions were

received with great

enthusiasm. One Gottfried

Wilhelm Fink, then editor

of the Allgemeine

musikalische Zeitung,

observed of these

transcriptions: Nothing

in recent memory has

caused such sensation and

enjoyment in both

pianists and audiences as

these arrangements...The

demand for them has in no

way been satisfied; and

it will not be until

these arrangements are

seen on pianos

everywhere. They have

indeed made quite a

splash. Eduard Hanslick,

never a sympathetic

critic of Liszt's music,

acknowledged thirty years

after the fact that,

Liszt's transcriptions of

Schubert Lieder were

epoch-making. There was

hardly a concert in which

Liszt did not have to

play one or two of

them--even when they were

not listed on the

program. These

transcriptions quickly

became some of his most

sough-after pieces,

despite their extreme

technical demands.

Leading pianists of the

day, such as Clara Wieck

and Sigismond Thalberg,

incorporated them into

their concert programs

immediately upon

publication. Moreover,

the transcriptions would

serve as inspirations for

other composers, such as

Stephen Heller, Cesar

Franck and later Leopold

Godowsky, all of whom

produced their own

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder. Liszt

would transcribe the

Lieder of other composers

as well, including those

by Mendelssohn, Chopin,

Anton Rubinstein and even

himself. Robert Schumann,

of course, would not be

ignored. The first

transcription of a

Schumann Lied was the

celebrated Widmung from

Myrten in 1848, the only

Schumann transcription

that Liszt completed

during the composer's

lifetime. (Regrettably,

there is no evidence of

Schumann's regard of this

transcription, or even if

he was aware of it.) From

the years 1848-1881,

Liszt transcribed twelve

of Robert Schumann's

Lieder (including one

orchestral Lied) and

three of Clara (one from

each of her three

published Lieder cycles);

he would transcribe no

other works of these two

composers. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions,

contrary to those of

Schubert, are literal

arrangements, posing, in

general, far fewer

demands on the pianist's

technique. They are

comparatively less

imaginative in their

treatment of the original

material. Additionally,

they seem to have been

less valued in their day

than the Schubert

transcriptions, and it is

noteworthy that none of

the Schumann

transcriptions bear

dedications, as most of

the Schubert

transcriptions do. The

greatest challenge posed

by Lieder transcriptions,

regardless of the

composer or the nature of

the transcription, was to

combine the vocal and

piano parts of the

original such that the

character of each would

be preserved, a challenge

unique to this form of

transcription. Each part

had to be intact and

aurally recognizable, the

vocal line in particular.

Complications could be

manifold in a Lied that

featured dissimilar

parts, such as Schubert's

Auf dem Wasser zu singen,

whose piano accompaniment

depicts the rocking of

the boat on the

shimmering waves while

the vocal line reflects

on the passing of time.

Similar complications

would be encountered in

Gretchen am Spinnrade, in

which the ubiquitous

sixteenth-note pattern in

the piano's right hand

epitomizes the

ever-turning spinning

wheel over which the

soprano voice expresses

feelings of longing and

heartache. The resulting

transcriptions for solo

piano would place

exceptional demands on

the pianist. The

complications would be

far less imposing in

instances in which voice

and piano were less

differentiated, as in

many of Schumann's Lieder

that Liszt transcribed.

The piano parts in these

Lieder are true

accompaniments for the

voice, providing harmonic

foundation and rhythmic

support by doubling the

vocal line throughout.

The transcriptions, thus,

are strict and literal,

with far fewer demands on

both pianist and

transcriber. In all of

Liszt's Lieder

transcriptions,

regardless of the way in

which the two parts are

combined, the melody

(i.e. the vocal line) is

invariably the focal

point; the melody should

sing on the piano, as if

it were the voice. The

piano part, although

integral to contributing

to the character of the

music, is designed to

function as

accompaniment. A singing

melody was a crucial

objective in

nineteenth-century piano

performance, which in

part might explain the

zeal in transcribing and

paraphrasing vocal music

for the piano. Friedrich

Wieck, father and teacher

of Clara Schumann,

stressed this point

repeatedly in his 1853

treatise Clavier und

Gesang (Piano and Song):

When I speak in general

of singing, I refer to

that species of singing

which is a form of

beauty, and which is a

foundation for the most

refined and most perfect

interpretation of music;

and, above all things, I

consider the culture of

beautiful tones the basis

for the finest possible

touch on the piano. In

many respects, the piano

and singing should

explain and supplement

each other. They should

mutually assist in

expressing the sublime

and the noble, in forms

of unclouded beauty. Much

of Liszt's piano music

should be interpreted

with this concept in

mind, the Lieder

transcriptions and opera

paraphrases, in

particular. To this end,

Liszt provided numerous

written instructions to

the performer to

emphasize the vocal line

in performance, with

Italian directives such

as un poco marcato il

canto, accentuato assai

il canto and ben

pronunziato il canto.

Repeated indications of

cantando,singend and

espressivo il canto

stress the significance

of the singing tone. As

an additional means of

achieving this and

providing the performer

with access to the

poetry, Liszt insisted,

at what must have been a

publishing novelty at the

time, on printing the

words of the Lied in the

music itself. Haslinger,

seemingly oblivious to

Liszt's intent, initially

printed the poems of the

early Schubert

transcriptions separately

inside the front covers.

Liszt argued that the

transcriptions must be

reprinted with the words

underlying the notes,

exactly as Schubert had

done, a request that was

honored by printing the

words above the

right-hand staff. Liszt

also incorporated a

visual scheme for

distinguishing voice and

accompaniment, influenced

perhaps by Chopin, by

notating the

accompaniment in cue

size. His transcription

of Robert Schumann's

Fruhlings Ankunft

features the vocal line

in normal size, the piano

accompaniment in reduced

size, an unmistakable

guide in a busy texture

as to which part should

be emphasized: Example 1.

Schumann-Liszt Fruhlings

Ankunft, mm. 1-2. The

same practice may be

found in the

transcription of

Schumann's An die Turen

will ich schleichen. In

this piece, the performer

must read three staves,

in which the baritone

line in the central staff

is to be shared between

the two hands based on

the stem direction of the

notes: Example 2.

Schumann-Liszt An die

Turen will ich

schleichen, mm. 1-5. This

notational practice is

extremely beneficial in

this instance, given the

challenge of reading

three staves and the

manner in which the vocal

line is performed by the

two hands. Curiously,

Liszt did not use this

practice in other

transcriptions.

Approaches in Lieder

Transcription Liszt

adopted a variety of

approaches in his Lieder

transcriptions, based on

the nature of the source

material, the ways in

which the vocal and piano

parts could be combined

and the ways in which the

vocal part could sing.

One approach, common with

strophic Lieder, in which

the vocal line would be

identical in each verse,

was to vary the register

of the vocal part. The

transcription of Lob der

Tranen, for example,

incorporates three of the

four verses of the

original Lied, with the

register of the vocal

line ascending one octave

with each verse (from low

to high), as if three

different voices were

participating. By the

conclusion, the music

encompasses the entire

range of Liszt's keyboard

to produce a stunning

climactic effect, and the

variety of register of

the vocal line provides a

welcome textural variety

in the absence of the

words. The three verses

of the transcription of

Auf dem Wasser zu singen

follow the same approach,

in which the vocal line

ascends from the tenor,

to the alto and to the

soprano registers with

each verse.

Fruhlingsglaube adopts

the opposite approach, in

which the vocal line

descends from soprano in

verse 1 to tenor in verse

2, with the second part

of verse 2 again resuming

the soprano register;

this is also the case in

Das Wandern from

Mullerlieder. Gretchen am

Spinnrade posed a unique

problem. Since the poem's

narrator is female, and

the poem represents an

expression of her longing

for her lover Faust,

variation of the vocal

line's register, strictly

speaking, would have been

impractical. For this

reason, the vocal line

remains in its original

register throughout,

relentlessly colliding

with the sixteenth-note

pattern of the

accompaniment. One

exception may be found in

the fifth and final verse

in mm. 93-112, at which

point the vocal line is

notated in a higher

register and doubled in

octaves. This sudden

textural change, one that

is readily audible, was a

strategic means to

underscore Gretchen's

mounting anxiety (My

bosom urges itself toward

him. Ah, might I grasp

and hold him! And kiss

him as I would wish, at

his kisses I should

die!). The transcription,

thus, becomes a vehicle

for maximizing the

emotional content of the

poem, an exceptional

undertaking with the

general intent of a

transcription. Registral

variation of the vocal

part also plays a crucial

role in the transcription

of Erlkonig. Goethe's

poem depicts the death of

a child who is

apprehended by a

supernatural Erlking, and

Schubert, recognizing the

dramatic nature of the

poem, carefully depicted

the characters (father,

son and Erlking) through

unique vocal writing and

accompaniment patterns:

the Lied is a dramatic

entity. Liszt, in turn,

followed Schubert's

characterization in this

literal transcription,

yet took it an additional

step by placing the

register of the father's

vocal line in the

baritone range, that of

the son in the soprano

range and that of the

Erlking in the highest

register, options that

would not have been

available in the version

for voice and piano.

Additionally, Liszt

labeled each appearance

of each character in the

score, a means for

guiding the performer in

interpreting the dramatic

qualities of the Lied. As

a result, the drama and

energy of the poem are

enhanced in this

transcription; as with

Gretchen am Spinnrade,

the transcriber has

maximized the content of

the original. Elaboration

may be found in certain

Lieder transcriptions

that expand the

performance to a level of

virtuosity not found in

the original; in such

cases, the transcription

approximates the

paraphrase. Schubert's Du

bist die Ruh, a paradigm

of musical simplicity,

features an uncomplicated

piano accompaniment that

is virtually identical in

each verse. In Liszt's

transcription, the

material is subjected to

a highly virtuosic

treatment that far

exceeds the original,

including a demanding

passage for the left hand

alone in the opening

measures and unique

textural writing in each

verse. The piece is a

transcription in

virtuosity; its art, as

Rosen noted, lies in the

technique of

transformation.

Elaboration may entail an

expansion of the musical

form, as in the extensive

introduction to Die

Forelle and a virtuosic

middle section (mm.

63-85), both of which are

not in the original. Also

unique to this

transcription are two

cadenzas that Liszt

composed in response to

the poetic content. The

first, in m. 93 on the

words und eh ich es

gedacht (and before I

could guess it), features

a twisted chromatic

passage that prolongs and

thereby heightens the

listener's suspense as to

the fate of the trout

(which is ultimately

caught). The second, in

m. 108 on the words

Betrogne an (and my blood

boiled as I saw the

betrayed one), features a

rush of

diminished-seventh

arpeggios in both hands,

epitomizing the poet's

rage at the fisherman for

catching the trout. Less

frequent are instances in

which the length of the

original Lied was

shortened in the

transcription, a tendency

that may be found with

certain strophic Lieder

(e.g., Der Leiermann,

Wasserflut and Das

Wandern). Another

transcription that

demonstrates Liszt's

readiness to modify the

original in the interests

of the poetic content is

Standchen, the seventh

transcription from

Schubert's

Schwanengesang. Adapted

from Act II of

Shakespeare's Cymbeline,

the poem represents the

repeated beckoning of a

man to his lover. Liszt

transformed the Lied into

a miniature drama by

transcribing the vocal

line of the first verse

in the soprano register,

that of the second verse

in the baritone register,

in effect, creating a

dialogue between the two

lovers. In mm. 71-102,

the dialogue becomes a

canon, with one voice

trailing the other like

an echo (as labeled in

the score) at the

distance of a beat. As in

other instances, the

transcription resembles

the paraphrase, and it is

perhaps for this reason

that Liszt provided an

ossia version that is

more in the nature of a

literal transcription.

The ossia version, six

measures shorter than

Schubert's original, is

less demanding

technically than the

original transcription,

thus representing an

ossia of transcription

and an ossia of piano

technique. The Schumann

Lieder transcriptions, in

general, display a less

imaginative treatment of

the source material.

Elaborations are less

frequently encountered,

and virtuosity is more

restricted, as if the

passage of time had

somewhat tamed the

composer's approach to

transcriptions;

alternatively, Liszt was

eager to distance himself

from the fierce

virtuosity of his early

years. In most instances,

these transcriptions are

literal arrangements of

the source material, with

the vocal line in its

original form combined

with the accompaniment,

which often doubles the

vocal line in the

original Lied. Widmung,

the first of the Schumann

transcriptions, is one

exception in the way it

recalls the virtuosity of

the Schubert

transcriptions of the

1830s. Particularly

striking is the closing

section (mm. 58-73), in

which material of the

opening verse (right

hand) is combined with

the triplet quarter notes

(left hand) from the

second section of the

Lied (mm. 32-43), as if

the transcriber were

attempting to reconcile

the different material of

these two sections.

Fruhlingsnacht resembles

a paraphrase by

presenting each of the

two verses in differing

registers (alto for verse

1, mm. 3-19, and soprano

for verse 2, mm. 20-31)

and by concluding with a

virtuosic section that

considerably extends the

length of the original

Lied. The original

tonalities of the Lieder

were generally retained

in the transcriptions,

showing that the tonality

was an important part of

the transcription

process. The infrequent

instances of

transposition were done

for specific reasons. In

1861, Liszt transcribed

two of Schumann's Lieder,

one from Op. 36 (An den

Sonnenschein), another

from Op. 27 (Dem roten

Roslein), and merged

these two pieces in the

collection 2 Lieder; they

share only the common

tonality of A major. His

choice for combining

these two Lieder remains

unknown, but he clearly

recognized that some

tonal variety would be

needed, for which reason

Dem roten Roslein was

transposed to C>= major.

The collection features

An den Sonnenschein in A

major (with a transition

to the new tonality),

followed by Dem roten

Roslein in C>= major

(without a change of key

signature), and

concluding with a reprise

of An den Sonnenschein in

A major. A three-part

form was thus established

with tonal variety

provided by keys in third

relations (A-C>=-A); in

effect, two of Schumann's

Lieder were transcribed

into an archetypal song

without words. In other

instances, Liszt treated

tonality and tonal

organization as important

structural ingredients,

particularly in the

transcriptions of

Schubert's Lieder cycles,

i.e. Schwanengesang,

Winterreise a... $32.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Rise Up Singing

Paroles et Accords [Partition]

Hal Leonard

The Group Singing Songbook. By Various. Vocal. Size 9.5x12 inches. 281 pages. Pu...(+)

The Group Singing

Songbook. By Various.

Vocal. Size 9.5x12

inches. 281 pages.

Published by Hal Leonard.

(1)$39.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Rise Up Singing

Paroles et Accords [Partition]

Hal Leonard

Arranged by Peter Blood, Annie Patterson. Vocal. Size 7.5x10.5 inches. 283 pages...(+)

Arranged by Peter Blood,

Annie Patterson. Vocal.

Size 7.5x10.5 inches. 283

pages. Published by Hal

Leonard.

(1)$34.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Der beleidigte Papagei

Piano seul [Partition + CD]

Breitkopf & Härtel

11 Miniaturen. Composed by Claus Kuhnl. Edition Breitkopf. In these eleven s...(+)

11 Miniaturen. Composed

by

Claus Kuhnl. Edition

Breitkopf.

In these eleven short

piano

pieces, the composer

follows

the cue of such

modern-day

masters as Olivier

Messiaen,

Karlheinz Stockhausen,

Helmut

Lachenmann and Nicolaus

A.

Huber.

Pedagogical. Breitkopf

and

Haertel #EB-9175.

Published

by Breitkopf and Haertel

$28.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 3 to 4 weeks | | | |

| Gallery of Memories

Peters

Voice (Soprano) SKU: PE.EP73717 For Soprano and Piano. Composed by...(+)

Voice (Soprano) SKU:

PE.EP73717 For

Soprano and Piano.

Composed by Jessica

Duchen and Roxanna

Panufnik. Solo Small

Ensembles; Vocal; Vocal

Score. Edition Peters.

Contemporary. Book. 28

pages. Edition Peters

#98-EP73717. Published by

Edition Peters

(PE.EP73717). ISBN

9790577023854. Almo

st 30 years before I

received this wonderful

co-commission, from

Presteigne and Oxford

Festivals, my friend and

librettist Jessica Duchen

sent me some of her

poems. I've been waiting

all this time for an

opportunity to set them

and Oxford Lieder

Festivals 2023 theme of

the Visual Arts provided

the perfect context,

especially as I could see

and hear so much colour

when reading

them.

Jessica has

cleverly created a highly

evocative narrative. This

song cycles story is

about preserving

something thats otherwise

gone forever, which

paintings, poetry and

music can all achieve.

Our heroine, touring an

art gallery, leaves the

official itinerary to

explore a long-ago

relationship through four

paintings she encounters,

imagining that she is

stepping into a different

time and place. Raindrop

Prelude evokes the

awakening of love, which

soon proves dangerous

(Playing with Fire); one

or both of them ran away

(Tarantella), but even

now she treasures a

transfigured, idealized

image (Neptune). Each

poem is prefaced with an

introduction as she walks

between the

pictures.

Im

hugely grateful to George

Vass (Presteigne) and

Sholto Kynoch (Oxford

Lieder) for commissioning

this and to Jessica for

her continuing

inspiration.

Roxanna

Panufnik, 5 April

2023

This product

is Printed on Demand and

may take several weeks to

fulfill. Please order

from your favorite

retailer. $25.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Everglades (River of Grass) [Conducteur]

Theodore Presser Co.

Band Bass Clarinet, Bassoon 1, Bassoon 2, Clarinet, Clarinet 1, Clarinet 2, Clar...(+)

Band Bass Clarinet,

Bassoon 1, Bassoon 2,

Clarinet, Clarinet 1,

Clarinet 2, Clarinet 3,

Contrabass Clarinet,

Contrabassoon, Double

Bass, English Horn,

Euphonium, Flute 1, Flute

2, Horn 1, Horn 2, Horn

3, Horn 4, Oboe 1, Oboe

2, Percussion 1 and more.

SKU: PR.16500101F

Mvt. 1 from Symphony

No. 6 (Three Places in

the East). Composed

by Dan Welcher. Full

score. 52 pages. Theodore

Presser Company

#165-00101F. Published by

Theodore Presser Company

(PR.16500101F). ISBN

9781491131725. UPC:

680160680252. Ever

since the success of my

series of wind ensemble

works Places in the West,

I've been wanting to

write a companion piece

for national parks on the

other side of the north

American continent. The

earlier work, consisting

of GLACIER, THE

YELLOWSTONE FIRES,

ARCHES, and ZION, spanned

some twenty years of my

composing life, and since

the pieces called for

differing groups of

instruments, and were in

slightly different styles

from each other, I never

considered them to be

connected except in their

subject matter. In their

depiction of both the

scenery and the human

history within these

wondrous places, they had

a common goal: awaking

the listener to the

fragile beauty that is in

them; and calling

attention to the ever

more crucial need for

preservation and

protection of these wild

places, unique in all the

world. With this new

work, commissioned by a

consortium of college and

conservatory wind

ensembles led by the

University of Georgia, I

decided to build upon

that same model---but to

solidify the process. The

result, consisting of

three movements (each

named for a different

national park in the

eastern US), is a

bona-fide symphony. While

the three pieces could be

performed separately,

they share a musical

theme---and also a common

style and

instrumentation. It is a

true symphony, in that

the first movement is

long and expository, the

second is a rather

tightly structured

scherzo-with-trio, and

the finale is a true

culmination of the whole.

The first movement,

Everglades, was the

original inspiration for

the entire symphony.

Conceived over the course

of two trips to that

astonishing place (which

the native Americans

called River of Grass,

the subtitle of this

movement), this movement

not only conveys a sense

of the humid, lush, and

even frightening scenery

there---but also an

overview of the entire

settling-of- Florida

experience. It contains

not one, but two native

American chants, and also

presents a view of the

staggering influence of

modern man on this

fragile part of the

world. Beginning with a

slow unfolding marked

Heavy, humid, the music

soon presents a gentle,

lyrical theme in the solo

alto saxophone. This

theme, which goes through

three expansive phrases

with breaks in between,

will appear in all three

movements of the

symphony. After the mood

has been established, the

music opens up to a rich,

warm setting of a

Cherokee morning song,

with the simple happiness

that this part of Florida

must have had prior to

the nineteenth century.

This music, enveloping

and comforting, gradually

gives way to a more

frenetic, driven section

representative of the

intrusion of the white

man. Since Florida was

populated and developed

largely due to the

introduction of a train

system, there's a

suggestion of the

mechanized iron horse

driving straight into the

heartland. At that point,

the native Americans

become considerably less

gentle, and a second

chant seems to stand in

the way of the intruder;

a kind of warning song.

The second part of this

movement shows us the

great swampy center of

the peninsula, with its

wildlife both in and out

of the water. A new theme

appears, sad but noble,

suggesting that this land

is precious and must be

protected by all the

people who inhabit it. At

length, the morning song

reappears in all its

splendor, until the

sunset---with one last

iteration of the warning

song in the solo piccolo.

Functioning as a scherzo,

the second movement,

Great Smoky Mountains,

describes not just that

huge park itself, but one

brave soul's attempt to

climb a mountain there.

It begins with three

iterations of the

UR-theme (which began the

first movement as well),

but this time as up-tempo

brass fanfares in

octaves. Each time it

begins again, the theme

is a little slower and

less confident than the

previous time---almost as

though the hiker were

becoming aware of the

daunting mountain before

him. But then, a steady,

quick-pulsed ostinato

appears, in a constantly

shifting meter system of

2/4- 3/4 in alteration,

and the hike has begun.

Over this, a slower new

melody appears, as the

trek up the mountain

progresses. It's a big

mountain, and the ascent

seems to take quite

awhile, with little

breaks in the hiker's

stride, until at length

he simply must stop and

rest. An oboe solo, over

several free cadenza-like

measures, allows us (and

our friend the hiker) to

catch our breath, and

also to view in the

distance the rocky peak

before us. The goal is

somehow even more

daunting than at first,

being closer and thus

more frighteningly steep.

When we do push off

again, it's at a slower

pace, and with more

careful attention to our

footholds as we trek over

broken rocks. Tantalizing

little views of the

valley at every

switchback make our

determination even

stronger. Finally, we

burst through a stand of

pines and----we're at the

summit! The immensity of

the view is overwhelming,

and ultimately humbling.

A brief coda, while we

sit dazed on the rocks,

ends the movement in a

feeling of triumph. The

final movement, Acadia,

is also about a trip. In

the summer of 2014, I

took a sailing trip with

a dear friend from North

Haven, Maine, to the

southern coast of Mt.

Desert Island in Acadia

National Park. The

experience left me both

exuberant and exhausted,

with an appreciation for

the ocean that I hadn't

had previously. The

approach to Acadia

National Park by water,

too, was thrilling: like

the difference between

climbing a mountain on

foot with riding up on a

ski-lift, I felt I'd

earned the right to be

there. The music for this

movement is entirely

based on the opening

UR-theme. There's a sense

of the water and the

mysterious, quiet deep

from the very beginning,

with seagulls and bell

buoys setting the scene.

As we leave the harbor,

the theme (in a canon

between solo euphonium

and tuba) almost seems as

if large subaquatic

animals are observing our

departure. There are

three themes (call them

A, B and C) in this

seafaring journey---but

they are all based on the

UR theme, in its original

form with octaves

displaced, in an

upside-down form, and in

a backwards version as

well. (The ocean, while

appearing to be

unchanging, is always

changing.) We move out

into the main channel

(A), passing several

islands (B), until we

reach the long draw that

parallels the coastline

called Eggemoggin Reach,

and a sudden burst of new

speed (C). Things

suddenly stop, as if the

wind had died, and we

have a vision: is that

really Mt. Desert Island

we can see off the port

bow, vaguely in the

distance? A chorale of

saxophones seems to

suggest that. We push off

anew as the chorale ends,

and go through all three

themes again---but in

different

instrumentations, and

different keys. At the

final tack-turn, there it

is, for real: Mt. Desert

Island, big as life.

We've made it. As we pull

into the harbor, where

we'll secure the boat for

the night, there's a

feeling of achievement.

Our whale and dolphin

friends return, and we

end our journey with

gratitude and

celebration. I am

profoundly grateful to

Jaclyn Hartenberger,

Professor of Conducting

at the University of

Georgia, for leading the

consortium which provided

the commissioning of this

work. $36.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| Symphony No. 6 [Conducteur]

Theodore Presser Co.

Band SKU: PR.16500104F Three Places in the East. Composed by Dan W...(+)

Band SKU:

PR.16500104F Three

Places in the East.

Composed by Dan Welcher.

Full score. Theodore

Presser Company

#165-00104F. Published by

Theodore Presser Company

(PR.16500104F). ISBN

9781491132159. UPC:

680160681082. Ever

since the success of my

series of wind ensemble

works Places in the West,

I've been wanting to

write a companion piece

for national parks on the

other side of the north

American continent. The

earlier work, consisting

of GLACIER, THE

YELLOWSTONE FIRES,

ARCHES, and ZION, spanned

some twenty years of my

composing life, and since

the pieces called for

differing groups of

instruments, and were in

slightly different styles

from each other, I never

considered them to be

connected except in their

subject matter. In their

depiction of both the

scenery and the human

history within these

wondrous places, they had

a common goal: awaking

the listener to the

fragile beauty that is in

them; and calling

attention to the ever

more crucial need for

preservation and

protection of these wild

places, unique in all the

world. With this new

work, commissioned by a

consortium of college and

conservatory wind

ensembles led by the

University of Georgia, I

decided to build upon

that same model---but to

solidify the process. The

result, consisting of

three movements (each

named for a different

national park in the

eastern US), is a

bona-fide symphony. While

the three pieces could be

performed separately,

they share a musical

theme---and also a common

style and

instrumentation. It is a

true symphony, in that

the first movement is

long and expository, the

second is a rather

tightly structured

scherzo-with-trio, and

the finale is a true

culmination of the whole.

The first movement,

Everglades, was the

original inspiration for

the entire symphony.

Conceived over the course

of two trips to that

astonishing place (which

the native Americans

called River of Grass,

the subtitle of this

movement), this movement

not only conveys a sense

of the humid, lush, and

even frightening scenery

there---but also an

overview of the entire

settling-of- Florida

experience. It contains

not one, but two native

American chants, and also

presents a view of the

staggering influence of

modern man on this

fragile part of the

world. Beginning with a

slow unfolding marked

Heavy, humid, the music

soon presents a gentle,

lyrical theme in the solo

alto saxophone. This

theme, which goes through

three expansive phrases

with breaks in between,

will appear in all three

movements of the

symphony. After the mood

has been established, the

music opens up to a rich,

warm setting of a

Cherokee morning song,

with the simple happiness

that this part of Florida

must have had prior to

the nineteenth century.

This music, enveloping

and comforting, gradually

gives way to a more

frenetic, driven section

representative of the

intrusion of the white

man. Since Florida was

populated and developed

largely due to the

introduction of a train

system, there's a

suggestion of the

mechanized iron horse

driving straight into the

heartland. At that point,

the native Americans

become considerably less

gentle, and a second

chant seems to stand in

the way of the intruder;

a kind of warning song.

The second part of this

movement shows us the

great swampy center of

the peninsula, with its

wildlife both in and out

of the water. A new theme

appears, sad but noble,

suggesting that this land

is precious and must be

protected by all the

people who inhabit it. At

length, the morning song

reappears in all its

splendor, until the

sunset---with one last

iteration of the warning

song in the solo piccolo.

Functioning as a scherzo,

the second movement,

Great Smoky Mountains,

describes not just that

huge park itself, but one

brave soul's attempt to

climb a mountain there.

It begins with three

iterations of the

UR-theme (which began the

first movement as well),

but this time as up-tempo

brass fanfares in

octaves. Each time it

begins again, the theme

is a little slower and

less confident than the

previous time---almost as

though the hiker were

becoming aware of the

daunting mountain before

him. But then, a steady,

quick-pulsed ostinato

appears, in a constantly

shifting meter system of

2/4- 3/4 in alteration,

and the hike has begun.

Over this, a slower new

melody appears, as the

trek up the mountain

progresses. It's a big

mountain, and the ascent

seems to take quite

awhile, with little

breaks in the hiker's

stride, until at length

he simply must stop and

rest. An oboe solo, over

several free cadenza-like

measures, allows us (and

our friend the hiker) to

catch our breath, and

also to view in the

distance the rocky peak

before us. The goal is

somehow even more

daunting than at first,

being closer and thus

more frighteningly steep.

When we do push off

again, it's at a slower

pace, and with more

careful attention to our

footholds as we trek over

broken rocks. Tantalizing

little views of the

valley at every

switchback make our

determination even

stronger. Finally, we

burst through a stand of

pines and----we're at the

summit! The immensity of

the view is overwhelming,

and ultimately humbling.

A brief coda, while we

sit dazed on the rocks,

ends the movement in a

feeling of triumph. The

final movement, Acadia,

is also about a trip. In

the summer of 2014, I

took a sailing trip with

a dear friend from North

Haven, Maine, to the

southern coast of Mt.

Desert Island in Acadia

National Park. The

experience left me both

exuberant and exhausted,

with an appreciation for

the ocean that I hadn't

had previously. The

approach to Acadia

National Park by water,

too, was thrilling: like

the difference between

climbing a mountain on

foot with riding up on a

ski-lift, I felt I'd

earned the right to be

there. The music for this

movement is entirely

based on the opening

UR-theme. There's a sense

of the water and the

mysterious, quiet deep

from the very beginning,

with seagulls and bell

buoys setting the scene.

As we leave the harbor,

the theme (in a canon

between solo euphonium

and tuba) almost seems as

if large subaquatic

animals are observing our

departure. There are

three themes (call them

A, B and C) in this

seafaring journey---but

they are all based on the

UR theme, in its original

form with octaves

displaced, in an

upside-down form, and in

a backwards version as

well. (The ocean, while

appearing to be

unchanging, is always

changing.) We move out

into the main channel

(A), passing several

islands (B), until we

reach the long draw that

parallels the coastline

called Eggemoggin Reach,

and a sudden burst of new

speed (C). Things

suddenly stop, as if the

wind had died, and we

have a vision: is that

really Mt. Desert Island

we can see off the port

bow, vaguely in the

distance? A chorale of

saxophones seems to

suggest that. We push off

anew as the chorale ends,

and go through all three

themes again---but in

different

instrumentations, and

different keys. At the

final tack-turn, there it

is, for real: Mt. Desert

Island, big as life.

We've made it. As we pull

into the harbor, where

we'll secure the boat for

the night, there's a

feeling of achievement.

Our whale and dolphin

friends return, and we

end our journey with

gratitude and

celebration. I am

profoundly grateful to

Jaclyn Hartenberger,

Professor of Conducting

at the University of

Georgia, for leading the

consortium which provided

the commissioning of this

work. $90.00 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| French Violin Music of the Baroque Era: , volume I

Violon et Piano [Partition]

G. Henle

Figured Bass Realization by S. Petrenz. By French Violin Music Of The Baroque Er...(+)

Figured Bass Realization

by S. Petrenz. By French

Violin Music Of The

Baroque Era. Edited by G.

Meyn-Beckmann. Violin.

Pages: Score = IX and 63

* Vl Part = 28 * BC Part

= 24. Urtext

edition-paper bound.

Published by G. Henle.

$42.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 24 hours - In Stock | | | |

| Fantasy-Variations on Two Themes

Orgue [Conducteur]

Zimbel Press

Organ SKU: SU.80101410 For Organ. Composed by Carson Cooman. Keybo...(+)

Organ SKU:

SU.80101410 For

Organ. Composed by

Carson Cooman. Keyboard,

Organ. Score. Zimbel

Press #80101410.

Published by Zimbel Press

(SU.80101410).

Fantasy-Variati

ons on Two Themes (2017)

for organ was written for

Heinrich Christensen in

celebration of his

significant 2017

birthday. The musical

material for the work

comprises two different

themes. The first is a

short melody by the

Danish composer Carl

Nielsen (1865-1931). (It

was a sketch originally

intended for inclusion

in, but ultimately left

out of, Nielsen's late

organ work 29 Little

Preludes.) This theme

represents Heinrich's

native Denmark. The

second theme is the

American folk-gospel hymn

Angel Band. This theme

represents Heinrich's

adopted American

homeland. It serves also

as a remembrance of our

dear mutual friend Harry

Lyn Huff (1952-2016), for

whom the tune was a

particular favorite. Both

these themes are

developed freely in a set

of alternating

fantasy-variations. The

opening variation begins

with a dramatic pedal

solo before quoting both

themes. The second

variation is a lyric

setting based on the

Nielsen melody. The third

is a jubilant hornpipe on

Angel Band. The fourth is

an aria on a

transformation of the

Nielsen melody. The fifth

is a gigue-toccata on

Angel Band. The sixth is

an atmospheric

contemplation: lush

chords in the manuals

move slowly and hint at

Angel Band while the

Nielsen melody is heard

for the first time in its

complete original form on

a high pedal stop. The

seventh and final

variation begins with a

brief evocation of the

harmonies of the late

Daniel Pinkham (a mentor

to both Heinrich and me)

before going on to return

dramatically and

jubilantly to the opening

music, bringing together

both themes again in a

bold conclusion.

Instrumentation: Organ

Duration: 15' Composed:

2017 Published by: Zimbel

Press. $16.95 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 2 to 3 weeks | | | |

| Marcel Tournier: Intermediate Pieces for Solo Harp, Volume II

Harpe

Carl Fischer

Chamber Music harp SKU: CF.H84 Composed by Marcel Tournier. Edited by Car...(+)

Chamber Music harp

SKU: CF.H84

Composed by Marcel

Tournier. Edited by Carl

Swanson. Collection -

Score. Carl Fischer Music

#H84. Published by Carl

Fischer Music (CF.H84).

ISBN 9781491165539.

UPC:

680160924530. Marce

l Tournier

(1879–1951) was

one of the most important

harpist/composers in the

history of the harp. Over

his long career, he added

a significant catalogue

of very beautiful works

to the harp repertoire.

Many of his solo works,

almost one hundred, have

been consistently in

print since they were

first published. But in

recent years harpist Carl

Swanson has discovered a

treasure trove of pieces

by Tournier heretofore

unknown and unpublished.

These include the

Déchiffrages in this

edition, as well as songs

set for voice, harp, and

string quartet, and

ensemble arrangements of

some of his most beloved

works.All of the works

that Carl Swanson found

were in manuscript only.

With the help of the

great harpist Catherine

Michel, he has put these

pieces into playable

form, and they are being

published for the very

first time. He and

Catherine often had to

re-notate passages to

show clearly how they

could be played, adding

fingerings and musical

nuances, tempos, pedals,

and pedal

diagrams.Tournier wrote

these pieces when he was

in his 20s, and before he

became the

impressionistic composer

those familiar with his

work know so well. They

are written in the late

nineteenth-century

romantic style that was

being taught at that time

at the Paris

Conservatory. They are

beautiful short,

intermediate level pieces

by a first rate composer,

and add much needed

repertoire to that level

of playing.

Marcel

Tournier

(1879–1951) was

one of the most important

harpist/composers in the

history of the harp. He

graduated from the Paris

Conservatory with a first

prize in harp in 1899. He

also studied composition

there and won a second

prize in the prestigious

Prix de Rome competition,

as well as a first prize

in the Rossini

competition, another

major composition

competition of the day.

From 1912 to 1948 he

taught the harp class at

the Paris Conservatory.

But composition, and

almost entirely,

composition for the harp,

was the main focus of his

life. His published

works, including many

works for solo harp, a

few for harp and other

instruments, and several

songs, number around one

hundred pieces.In 2019,

while researching

Tournier for my edition

MARCEL TOURNIER: 10

Pieces for Solo Harp, I

discovered that there was

a significant list of

pieces by this composer

that had never been

published and were not

included on any inventory

of his music. Principal

on this list were his

déchiffrages

(pronounced

day-she-frahge, like the

second syllable in the

word garage).The word

déchiffrage means

sight-reading exercise,

and that was their

original purpose.

Tournier numbered and

dated these pieces, with

dates ranging from 1900

to 1910, indicating that

they were in all

likelihood written for

Alphonse

Hasselmans’ class

at the Paris

Conservatory. Tournier

was probably told how

long to make each one,

and how difficult. They

range in length from two

to four pages, with only

one in the whole series

extending to five, and

from thirty to fifty-five

measures, with only one

extending to eight-five.

The level of difficulty

for the whole series is

intermediate, with some

at the easier end, and

others at the middle or

upper end.We don’t

know if they were

intended to test students

trying to enter the harp

class, or if they were

used to test students in

the class as they played

their exams. The fact

that they were never

published means that

students had to not only

sight read them, but

sight read them in

manuscript form!I worked

from digital images of

the original manuscripts,

which are in the private

music library of a

harpist in France. She

had twenty-seven of these

pieces, and this edition

is the second in a series

of three that will

publish, for the first

time, all of the ones

that I have found thus

far. The manuscripts

themselves consist of

little more than notes on

the page: no pedals

written in, no

fingerings, few if any

musical nuances and tempo

markings, and no clear

indication as to which

hand plays which notes.

These would have been

difficult to sight read

indeed! My collaborator

Catherine Michel and I

added musical nuances,

fingerings, pedals and

pedal diagrams, and tempo

indications to put them

into their current

condition.At the time

these were written,

Tournier would have been

in his twenties, having

just graduated from the

harp class himself

(1899), and might still

have been in the

composition class. These

are the earliest known

pieces that he wrote, and

they were written at the

very beginning of a

cultural revolution and

upheaval in Paris that

was to completely and

profoundly alter musical

composition. Tournier

himself would eventually

be caught up in this new

way of composing. But not

yet.All of the

déchiffrages are

written in the late

romantic style that was

being taught at that time

at the Paris

Conservatory. Each one is

built on a clear musical

idea, and the variety

over the whole series

makes them wonderful to

listen to as well as to

learn. They are also

great technical lessons

for intermediate level

players.The obvious

question is: Why

didn’t Tournier

publish these pieces, and

why didn’t he list

them on his own inventory

of his music? Actually,

four of them were

published, with small

changes, as his

collection Four Preludes,

Op. 16. These came from

the ones that will be in

volume three of this

series from Carl Fischer.

His first large piece,

Theme and Variations, was

published in 1908, and

his two best known and

frequently played pieces,

Féerie and Au Matin,

followed in 1912 and 1913

respectively. We can only

speculate because there

is so much still unknown

about Tournier and about

these unpublished pieces.

He may have looked at

them, fresh out of school

as he was, as simply a

way to make some quick

money. The first several

pieces that he did

publish are much longer

than any of the

déchiffrages. So it

could be that, because of

their shorter length, as

well as the earlier

musical style that he was

moving away from, he

chose not to publish any

more of them. We may

never know the full

story. But all these

years later, more than a

century after they were

composed, we can listen

to them for their own

merits, and not measured

against whatever else was

going on at the time. The

numbers on these pieces

are the ones that

Tournier assigned to

them, and the gaps

between some of the

numbers suggest that

there are perhaps thirty

or more of these pieces

still to be found, if

they still exist. They

will, in all likelihood,

be found, as these were,

in private collections of

harp music, not in

institutional libraries.

We can only hope that

more of them will be

located in years to

come.—Carl

SwansonGlossary of French

Musical TermsTournier was

very precise about how he

wanted his pieces played,

and carefully

communicated this with

many musical indications.

He used standard Italian

words, but also used

French words and phrases,

and occasionally mixed

both together. It is

extremely important to

observe and understand

everything that he put on

the page.Here is a list

of the French words and

phrases found in the

pieces in this edition,

with their

translation.bien

chanté well sung,

melodiousdécidé

firm, resolutediminu peu

à peu becoming softer

little by littleen

diminuant becoming

softeren riten. slowing

downen se perdant dying

awayGaiement gayly,

lightlygracieusement

gracefully,

elegantlyLéger light,

quickLent slowmarquez le

chant emphasize the

melodyModéré at a

moderate tempopeu Ã

peu animé more lively,

little by littleplus lent

slowerRetenu held

backsans lenteur without

slownesssans retinir

without slowing downsec

drily, abruptlysoutenu

sustained, heldtrès

arpegé very

arpeggiatedTrès

Modéré Very

moderate tempoTrès peu

retenu slightly held

backTrès soutenu very

sustainedun peu retenu

slightly held back. $19.99 - Voir plus => AcheterDélais: 1 to 2 weeks | | | |

| Acadia [Conducteur]

Theodore Presser Co.

Band Bass Clarinet, Bassoon 1, Bassoon 2, Clarinet, Clarinet 1, Clarinet 2, Clar...(+)

Band Bass Clarinet,

Bassoon 1, Bassoon 2,

Clarinet, Clarinet 1,

Clarinet 2, Clarinet 3,

Contrabass Clarinet,

Contrabassoon, Double

Bass, English Horn,

Euphonium, Flute 1, Flute

2, Horn 1, Horn 2, Horn

3, Horn 4, Oboe 1, Oboe

2, Percussion 1 and more.

SKU: PR.16500103F

Mvt. 3 from Symphony

No. 6 (Three Places in

the East). Composed

by Dan Welcher. Full

score. 60 pages. Theodore

Presser Company

#165-00103F. Published by

Theodore Presser Company

(PR.16500103F). ISBN

9781491131763. UPC:

680160680290. Ever

since the success of my

series of wind ensemble

works Places in the West,

I've been wanting to

write a companion piece

for national parks on the

other side of the north

American continent. The

earlier work, consisting

of GLACIER, THE

YELLOWSTONE FIRES,

ARCHES, and ZION, spanned

some twenty years of my

composing life, and since

the pieces called for

differing groups of

instruments, and were in

slightly different styles

from each other, I never

considered them to be

connected except in their

subject matter. In their

depiction of both the

scenery and the human

history within these

wondrous places, they had

a common goal: awaking

the listener to the

fragile beauty that is in

them; and calling

attention to the ever

more crucial need for

preservation and

protection of these wild

places, unique in all the

world. With this new

work, commissioned by a

consortium of college and

conservatory wind

ensembles led by the

University of Georgia, I

decided to build upon

that same model---but to

solidify the process. The

result, consisting of

three movements (each

named for a different

national park in the

eastern US), is a

bona-fide symphony. While

the three pieces could be

performed separately,

they share a musical

theme---and also a common

style and

instrumentation. It is a

true symphony, in that

the first movement is

long and expository, the

second is a rather

tightly structured

scherzo-with-trio, and

the finale is a true

culmination of the whole.

The first movement,

Everglades, was the

original inspiration for

the entire symphony.

Conceived over the course

of two trips to that

astonishing place (which

the native Americans

called River of Grass,

the subtitle of this

movement), this movement

not only conveys a sense

of the humid, lush, and

even frightening scenery

there---but also an

overview of the entire

settling-of- Florida

experience. It contains

not one, but two native

American chants, and also

presents a view of the

staggering influence of

modern man on this

fragile part of the

world. Beginning with a

slow unfolding marked

Heavy, humid, the music

soon presents a gentle,

lyrical theme in the solo

alto saxophone. This