Don Carlo Gesualdo (1566 - 1613)

Italie

Italie

Italie

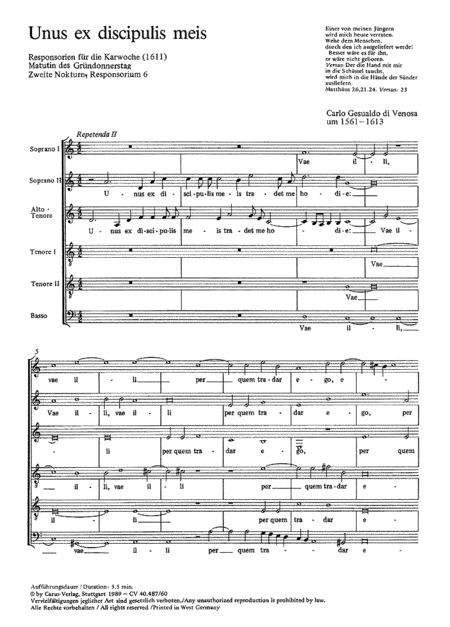

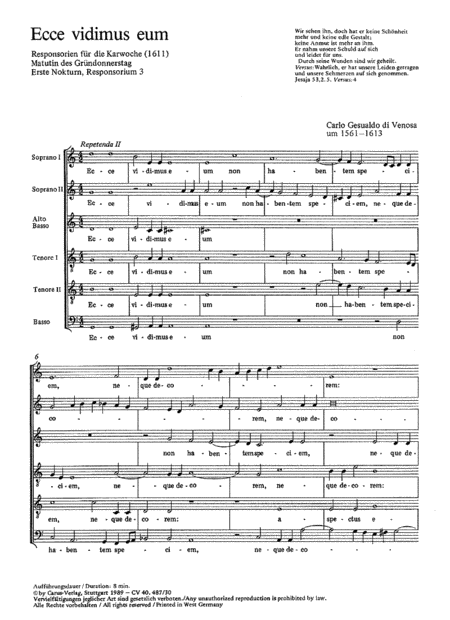

ItalieCarlo Gesualdo, known as Gesualdo da Venosa (March 8, 1566 ? September 8, 1613), Prince of Venosa and Count of Conza, was an Italian music composer, lutenist and nobleman of the late Renaissance. He is famous for his intensely expressive madrigals, which use a chromatic language not heard again until the 19th century; and also for committing what are amongst the most notorious murders in musical history.

The evidence that Gesualdo was tortured by guilt for the remainder of his life is considera ... (Read all)

Source : Wikipedia

The evidence that Gesualdo was tortured by guilt for the remainder of his life is considera ... (Read all)

Source : Wikipedia

FREE SHEET MUSIC

Active criterias:

Search

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

SHEET MUSIC

SHEET MUSIC